The Product Is You

The illusion of paying nothing (zero costs): why market performance is not a straight line, and real deception is simple thinking

In recent years, thanks to the rise of shallow financial education, digital platforms and hyper-simplified social media communication of the «markets always go up» variety, a new ideological front has formed: the champions of zero cost. A new generation of self-proclaimed whistleblowers has begun to point the finger at everything that is expensive in the world of investment. Active funds? Scam. Insurance policies? Legalized theft. Financial advice? Hidden costs. Only ETFs, only very low TERs, only passive management.

This phenomenon didn’t come out of nowhere. It is the product of a digital culture that has replaced in-depth study with the search for simple phrases and immediately shareable slogans. In the past, to form an opinion on the markets, an investor had to read books, take courses and consult with professionals. Today, all you have to do is scroll through a feed to find hundreds of pieces of content that, in a matter of seconds, offer absolute truths in the form of viral posts. It is a process fuels polarization: there are the advocates of active management and value of advice; on the other hand, there are the supporters of extreme cost reduction, as if cost were the only parameter that matters.

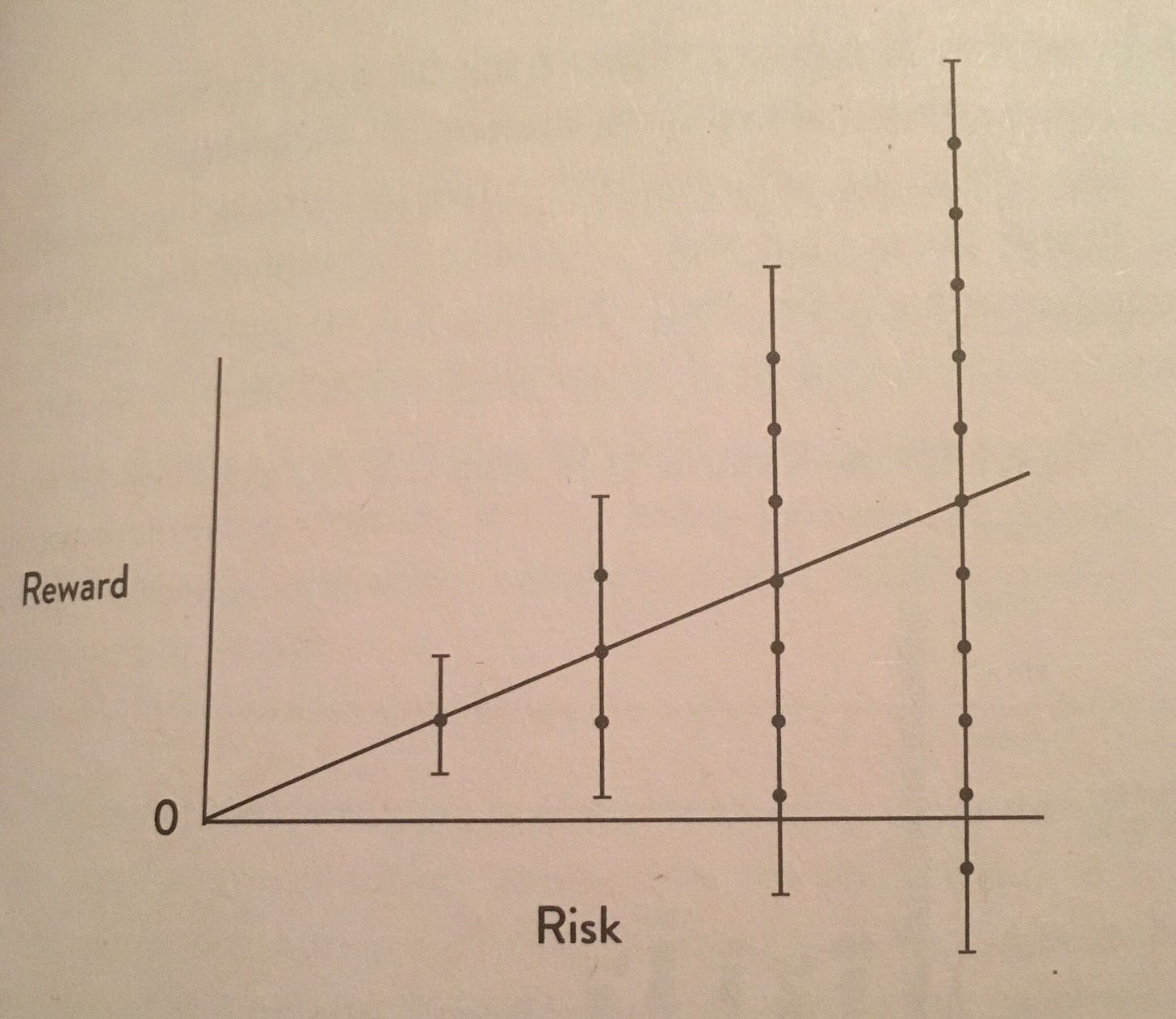

But in this systematic and generalized attack, the central point is being lost sight of: returns are not linear. And when returns are not linear, the weight of costs also changes radically. It is a concept that escapes many because the human mind tends to reason by averages, by simple and linear patterns, while markets are anything but linear. Let's take a look at it together.

In questi anni, complice l’aumento dell’educazione finanziaria superficiale, delle piattaforme digitali e di una comunicazione social iper-semplificata del tipo «i mercati salgono sempre», si è andato formando un nuovo fronte ideologico: quello dei paladini del costo zero. Una nuova generazione di smascheratori autoproclamati ha iniziato a puntare il dito contro tutto ciò che è costoso nel mondo degli investimenti. Fondi attivi? Truffa. Polizze? Furto legalizzato. Consulenza finanziaria? Costo occulto. Solo ETF, solo TER bassissimi, solo gestione passiva.

Questo fenomeno non è nato dal nulla. È figlio di una cultura digitale che ha sostituito lo studio approfondito con la ricerca di frasi semplici e slogan immediatamente condivisibili. In passato, per formarsi un’idea sui mercati, un investitore doveva leggere libri, seguire corsi, confrontarsi con professionisti. Oggi basta scorrere un feed per trovare centinaia di contenuti che, in pochi secondi, offrono verità assolute sotto forma di post virali. È un processo che alimenta la polarizzazione: da un lato i fautori della gestione attiva e del valore della consulenza, dall’altro i sostenitori della riduzione estrema dei costi, come se il costo fosse l’unico parametro che conta.

Ma in questo attacco sistematico e generalizzato si sta perdendo di vista il punto centrale: i rendimenti non sono lineari. E quando il rendimento non è lineare, anche il peso dei costi cambia radicalmente. È un concetto che sfugge a molti perché la mente umana tende a ragionare per medie, per schemi semplici e lineari, mentre i mercati sono tutt’altro che lineari. Vediamolo insieme.

Do you know what to do when it matters?

One of the most common arguments used by those who promote only low-cost instruments is the following: «If the market averages 6% per year and you pay 1.5% per year in costs, you will lose hundreds of thousands of dollars in the long run». It's a perfectly valid argument, but only on Excel. In reality, market doesn’t return consistent returns: the average is an abstraction, not a trajectory, and this completely changes the dynamics of the investment.

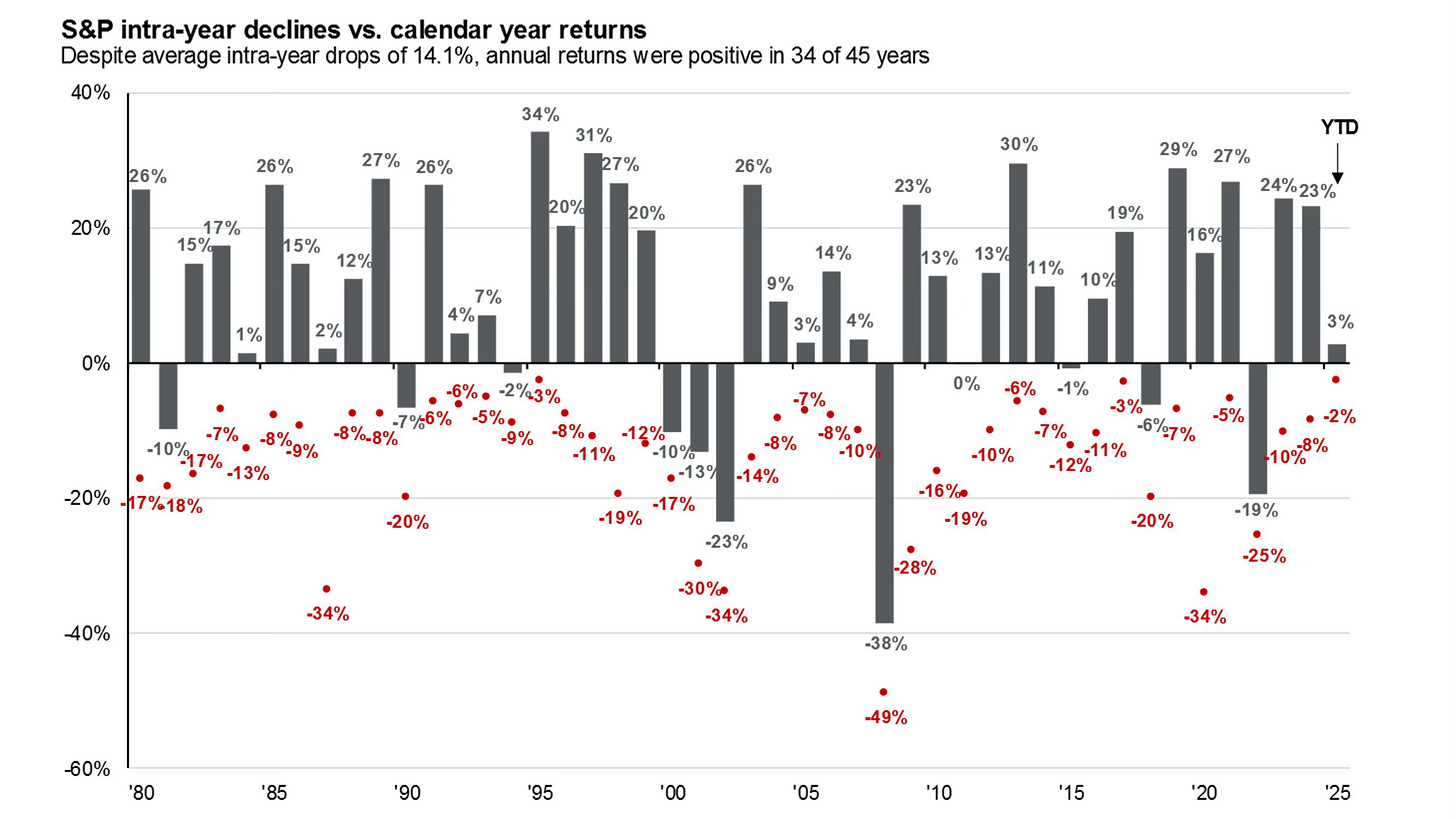

A historical chart of the S&P500 clearly shows how even within a positive decade there can be years with double-digit declines. Those moments of decline, if not managed correctly, can turn into real and definitive losses for those who let themselves be guided by emotions (I discussed this in detail in a recent article, «Law of large losses»). This is the crux of the matter: average calculation ignores volatility and the investor's behavior in the face of that volatility.

Imagine two investors, both with the same portfolio and same time horizon. The first one starts in a favorable decade, full of rallies and remains invested, while the second one starts when market is flat or declining for the first few years, perhaps makes a few wrong moves, but then recovers. The result: same instrument, same cost, but completely different final returns. Now, let's add a variable: the investor who paid more got support from a financial advisor who kept them steady during tough times; the other, thinking they were saving money, gave in to their emotions and sold. Who really paid the highest price?

The history of the markets is full of similar examples. In 2008, during the financial crisis, many DIY investors sold in the midst of panic, turning a temporary loss into permanent damage. Even a very famous Robo-Advisor in Italy implemented a portfolio rotation strategy (notifying clients with a letter of apology for the poor returns, ed.) by selling stocks at their absolute lows in 2020 and buying bonds at negative rates, at the worst possible time. In those cases, the cost of consulting turned into a real gain, simply by avoiding an irreversible mistake driven by the emotion of the moment.

Sai cosa fare nei momenti che contano?

Uno degli argomenti più usati da chi promuove solo strumenti low-cost è il seguente: «Se il mercato fa in media il 6% annuo e tu paghi l’1,5% all’anno di costi, nel lungo periodo perderai centinaia di migliaia di euro». È un ragionamento che funziona perfettamente, ma solo su Excel. Nella realtà, il mercato non restituisce rendimenti in modo costante: la media è un’astrazione, non una traiettoria, e ciò cambia completamente la dinamica dell’investimento.

Un grafico storico dell’S&P500 mostra chiaramente come anche all’interno di un decennio positivo ci possano essere anni con crolli a doppia cifra. Quei momenti di discesa, se non gestiti correttamente, possono trasformarsi in perdite reali e definitive per chi si lascia guidare dalle emozioni (ne ho parlato in maniera dettagliata in un recente articolo «La legge delle grandi perdite»). Questo è il nodo: il calcolo medio ignora la volatilità e il comportamento dell’investitore di fronte a quella volatilità.

Immagina due investitori, entrambi con lo stesso portafoglio e lo stesso orizzonte temporale. Uno parte in un decennio favorevole, pieno di rally, e resta investito, l’altro inizia quando il mercato è piatto o in calo per i primi anni, magari sbaglia qualche movimento, poi recupera. Risultato: stesso strumento, stesso costo, ma rendimenti finali completamente diversi. Ora, aggiungiamo una variabile: l’investitore che ha pagato di più ha ottenuto un supporto da parte del consulente finanziario che lo ha tenuto fermo nei momenti difficili; l’altro, convinto di risparmiare, ha ceduto all’emotività e ha disinvestito. Chi ha davvero pagato il prezzo più alto?

La storia dei mercati è piena di esempi simili. Nel 2008, durante la crisi finanziaria, molti investitori fai da te vendettero nel pieno del panico, trasformando una perdita temporanea in un danno permanente. Addirittura un Robo-Advisor molto famoso in Italia, attuò una strategia di rotazione di portafoglio (avvisando i clienti con una lettera di scuse per i pessimi rendimenti, ndr) vendendo azionario sui minimi assoluti del 2020 e comprando obbligazionario a tassi negativi, nel peggior momento possibile. In quei casi, il costo della consulenza si è trasformato in un guadagno reale, semplicemente evitando un errore irreversibile guidato dall’emotività del momento.

TER is not everything: an explanatory example

One of the concepts least understood by retail investors is that of «return sequence». In most cases, investors are unaware the order in which positive and negative returns occur has a crucial impact on the final outcome of an investment, especially if regular deposits or withdrawals are made. Let's take another explanatory example:

Scenario A: first 5 years negative, last 5 years positive

Scenario B: first 5 years positive, last 5 years negative

Same annual average, same TER, but completely different final results, especially if you have made a Dollar-Cost Averaging plan or retired and started withdrawing funds in the meantime. The real risk for investors is not the costs, but sequence of returns, and no ETF can protect you from this. On the contrary, good advice, robust management, and less flexible but more stable instruments can make a huge difference. But what is TER?

When we talk about TER, which stands for Total Expense Ratio, we are referring to the total annual cost of a fund or ETF, expressed as a percentage of the average assets under management. In other words, it is the bill that manager presents to us every year to keep the investment machine running: it includes management fees, administrative fees, and ordinary operating costs. Performance fees and transaction costs related to the purchase or sale of securities in the portfolio are not included.

Many people focus exclusively on the TER because it is an easy number to understand and compare. However, this approach ignores the most important question: what do I get in return for that cost? A fund with a higher TER may include protection strategies, active rebalancing, proprietary research, and hedging instruments. These are elements are not visible in a prospectus but affect the ability to navigate the markets in adverse conditions.

Il TER non è tutto: un esempio chiarificatore

Uno dei concetti meno compresi dagli investitori retail è quello della «sequenza dei rendimenti». Nella maggior parte dei casi infatti, si ignora che l’ordine con cui arrivano i rendimenti positivi e negativi ha un impatto cruciale sull’esito finale di un investimento, soprattutto se si fanno versamenti o prelievi regolari. Facciamo un altro esempio chiarificatore:

Scenario A: primi 5 anni negativi, ultimi 5 positivi

Scenario B: primi 5 positivi, ultimi 5 negativi

Stessa media annua, stesso TER, ma risultati finali completamente diversi, soprattutto se nel frattempo si è fatto un PAC o si è andati in pensione e si comincia a prelevare. Il rischio reale, per l’investitore, non sono i costi, bensì la sequenza dei rendimenti e nessun ETF ti protegge da questo. Al contrario, una buona consulenza, una gestione robusta, strumenti meno flessibili ma più stabili possono fare una differenza enorme. Ma cos’è il TER?

Quando parliamo di TER, acronimo di Total Expense Ratio, ci riferiamo al costo complessivo annuo di un fondo o ETF, espresso in percentuale rispetto al patrimonio medio gestito. È, in altre parole, il conto che il gestore ci presenta ogni anno per far funzionare la macchina dell’investimento: dentro ci troviamo le spese di gestione, quelle amministrative e i costi operativi ordinari. Restano invece fuori le commissioni di performance e i costi di transazione legati all’acquisto o alla vendita dei titoli in portafoglio.

Molti si concentrano esclusivamente sul TER perché è un numero facile da capire e da confrontare. Tuttavia, questo approccio ignora la domanda più importante: cosa ricevo in cambio di quel costo? Un fondo con TER più alto può includere strategie di protezione, ribilanciamenti attivi, ricerca proprietaria, strumenti di copertura. Sono elementi che non si vedono in un prospetto ma che incidono sulla capacità di navigare i mercati in condizioni avverse.

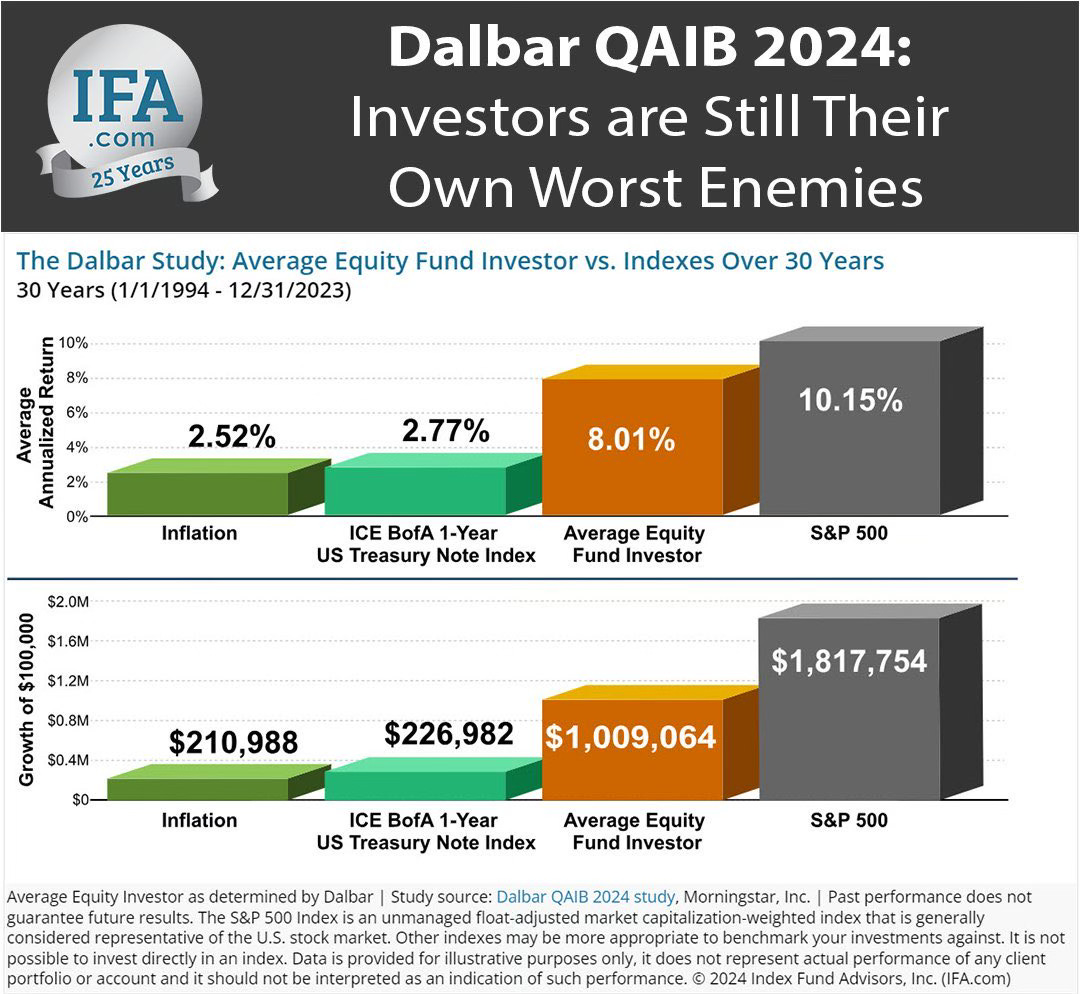

The DALBAR study that investors ignore

At this point, it is clear that costs are not the absolute evil, but only one of many elements to be evaluated in an investment project. However, the ideology of «everything for free» has taken root deeply, often because it seems logical and intuitive. But finance is not intuitive, and paying less doesn’t mean earning more.

According to DALBAR's annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) report, the average investor earned a return of about 16% in 2024, well below the 25% return of the S&P500 index. In 2023, the gap was already significant. At the heart of methodology is the dollar-weighted approach, which calculates the real return that investors earn by taking into account inflows and outflows from funds: this penalizes those who enter during periods of euphoria and exit in panic, providing an accurate reflection of true return earned, not just theoretical performance of the fund. Reducing costs is important, but it is not enough. It is behavioral discipline, staying invested, avoiding chasing rallies or fleeing during corrections, that really makes the difference; even an expensive instrument can beat a cheap one if the investor knows how to stay the course.

As DALBAR study also shows, investors who have traded in flexible and inexpensive instruments have often achieved lower returns than those who have invested in more expensive instruments are less prone to behavioral errors. Why? Because the average investor is not rational, and it is not the box they invest in that makes the difference, but how they behave while are in it.

The most interesting part of this phenomenon is that many of those who set themselves up as exposers of the system have, in turn, become new salespeople, only today they offer a free ebook, a $97 course, or a revolutionary platform with zero commissions. In short, they have changed their clothes, but the goal is still to sell something disguised as absolute truth. And just like years ago with door-to-door salespeople selling vacuum cleaners and insurance, today these new gurus sell you the purity of passive investment, the ethics of low TER, and myth of conscious DIY. But in the end, they too are monetizing your attention, your uncertainty, and your fear.

Lo studio DALBAR che gli investitori ignorano

A questo punto è chiaro che i costi non sono il male assoluto, ma solo uno dei tanti elementi da valutare in un progetto di investimento. Tuttavia, l’ideologia del tutto gratis ha attecchito in profondità, spesso perché appare logica e intuitiva. Ma la finanza non è intuitiva e pagare poco non significa guadagnare di più.

Secondo il rapporto annuale Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) di DALBAR, l’investitore medio ha ottenuto un rendimento del 16% circa nel 2024, ben al di sotto del 25% dell’indice S&P500. Nel 2023, il divario era già significativo. Nel cuore della metodologia c’è l’approccio dollar-weighted, che calcola il rendimento reale che l’investitore ottiene tenendo conto dei flussi in entrata e in uscita dai fondi: questo penalizza chi entra nei periodi di euforia e esce nel panico, offrendo uno specchio fedele del vero rendimento ottenuto, non solo della performance teorica del fondo. Ridurre i costi è importante, ma non basta. È la disciplina comportamentale, restare investiti, evitare di rincorrere i rialzi o fuggire durante le correzioni, che fa davvero la differenza; anche uno strumento caro può battere uno economico se l’investitore sa mantenere la rotta.

Come dimostra anche lo studio DALBAR, gli investitori che hanno operato in strumenti flessibili e poco costosi spesso hanno ottenuto rendimenti inferiori rispetto a quelli che hanno investito in strumenti più costosi ma meno soggetti a errori comportamentali. Motivo? Perché l’investitore medio non è razionale e la differenza non la fa la scatola in cui investe, ma il modo in cui si comporta mentre ci sta dentro.

La parte più interessante di questo fenomeno è che molti di coloro che si ergono a smascheratori del sistema sono diventati, a loro volta, nuovi venditori, solo che oggi propongono un ebook gratuito, un corso a 97€ o una piattaforma rivoluzionaria con zero commissioni. Insomma, hanno cambiato il vestito, ma l’obiettivo è sempre vendere qualcosa mascherato da verità assoluta. E proprio come accadeva anni fa con i promotori porta a porta che ti vendevano aspirapolveri e assicurazioni, oggi questi nuovi guru ti vendono la purezza dell’investimento passivo, l’etica del TER basso, il mito del fai da te consapevole. Ma alla fine, anche loro stanno monetizzando la tua attenzione, la tua incertezza, la tua paura.

If a service is free, YOU are the product

It's a sentence that makes us smile when we think of social media, but it becomes much less funny when it comes to money. In financial markets, chasing zero cost can mean paying in another currency: lost returns, missed opportunities and wrong choices. Truth is that price doesn’t tell the whole story: what really matters is the quality of the product, soundness of the strategy and expertise of those who support you. Because a low-cost product can turn out to be very expensive, and one that seems expensive can be the best investment of your life. In this regard, financial advice is often criticized because it costs money. But what does it really cost?

A human, personalized service that helps you build a solid, consistent, sustainable plan can handle the downs as well as the ups, guides you when there is uncertainty, educates you, empowers you. Anyone who wants to eliminate all this to cut costs is, in my opinion, making a strategic mistake. Because the risk of losing 10 or 20 years of real returns along the way due to a wrong reaction is far more serious than paying an extra percentage point each year. Markets don’t reward those who pay less, but those who know how to wait, how to understand, how to stay. And to do that, you need a guide, not an Excel file. Maybe even helps to understand and explore topics are a little more complex than how they are sold, but it's not all that easy and automated. After all, if it were, we would be talking about multimillionaires in every corner of the planet.

Those who profess a totally passive attitude towards investment are also the same ones who jump on the new sector ETF, the new trendy product, or worse still, try to time the market during crashes. In my previous articles, I have spoken openly about Lump-Sum Investment or Dollar-Cost Averaging and what is best for investors in general: it is not the product makes the difference, but attitude that repays the effort.

So, the next time someone talks to you about a 6% annual return for 40 years and gives you a clear calculation of how much you would have lost due to a 1% cost, stop for a moment. Ask them: in what year did you start? How many crashes have you been through? How many times have you resisted the temptation to sell? Because that's where the real difference lies, and no TER alone can tell you that.

Se un servizio è gratis, il prodotto sei TU

È una frase che fa sorridere finché pensiamo ai social, ma diventa molto meno divertente quando si parla di soldi. Nei mercati finanziari, inseguire il costo zero può significare pagare in un’altra moneta: quella dei rendimenti persi, delle occasioni mancate e delle scelte sbagliate. La verità è che il prezzo non dice tutto: ciò che conta davvero è la qualità del prodotto, la solidità della strategia e la competenza di chi ti affianca. Perché un prodotto a basso costo può rivelarsi carissimo, e uno che sembra costoso può essere il migliore investimento della tua vita. In merito a questo, la consulenza finanziaria è spesso attaccata perché costa. Ma cosa costa davvero?

Un servizio umano, personalizzato, che ti aiuta a costruire un piano solido, coerente, sostenibile, in grado di affrontare le discese e non solo le salite, che ti guida quando c’è incertezza, che ti educa, che ti responsabilizza. Chi vuole eliminare tutto questo per tagliare il costo, a mio parere commette un errore strategico. Perché il rischio di perdere per strada 10 o 20 anni di rendimento reale a causa di una reazione sbagliata è ben più grave di pagare un punto percentuale in più ogni anno. I mercati non premiano chi paga meno, ma chi sa aspettare, chi sa capire, chi sa restare. E per farlo, serve una guida, non un file Excel. Magari anche quello, aiuta a capire e approfondire temi un pochino più complessi di come vengono venduti, ma non è tutto così facile e automatizzatile. Del resto, se lo fosse staremo parlando di multimilionari in ogni angolo del pianeta.

Coloro che professano l’atteggiamento totalmente passivo verso l’investimento, sono anche gli stessi che saltano sul nuovo ETF settoriale, sul nuovo prodotto di tendenza, o peggio ancora cercando di fare timing sul mercato durante i crolli. Nei miei articoli precedenti ho parlato apertamente di PIC o PAC e di cosa sia meglio per l’investitore in generale: non è il prodotto che fa la differenza ma è l’atteggiamento che ripaga gli sforzi.

Quindi, la prossima volta che qualcuno vi parla di un rendimento 6% annuo per 40 anni e vi fa il calcolo preciso di quanto avreste perso a causa di un 1% di costo, fermatevi un attimo. Chiedetegli: in quale anno hai iniziato tu? Quanti crolli hai attraversato? Quante volte hai resistito alla tentazione di vendere? Perché lì si gioca la vera differenza e nessun TER, da solo, può raccontarla.