Law of Large Losses

Why what goes down in the markets doesn't always come back up

There is an uncomfortable truth that every investor, sooner or later, is forced to face. It is a mathematical truth, but also a deeply psychological one. It concerns the dynamics of losses in financial markets and relationship that every portfolio, and every mind, has with them. In a world where financial communication is dominated by charts celebrating gains and stories of rapid capital multiplication, there is a silent and relentless law: the large losses.

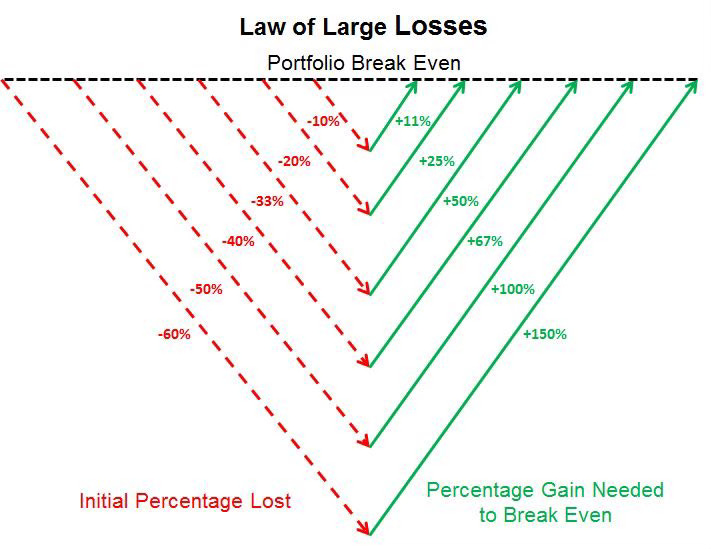

The principle behind it is as simple as it is counterintuitive. When an asset, a security, or an entire portfolio suffers a loss, the gain needed to recover that loss is not symmetrical. Losing 10% and gaining 10% is not the same as returning to the starting point. On the contrary, recovery becomes increasingly difficult as the initial loss increases. This asymmetry, visually well represented in the chart known as the «Law of Large Losses», is a mathematical foundation that every investor should internalize before even thinking about performance.

In the chart accompanying these reflections, we see a series of trajectories that develop from different initial losses. For a 10% decline, rebound needed to return to the initial level is just over 11%. But if the loss becomes 50%, the gain required to break even doubles to 100%. And if capital is reduced by 60%, the recovery will have to be 150% to return to the break-even point. Compound interest, but in reverse.

The message, therefore, is not just mathematical: it is existential. As you fall, climbing back up becomes exponentially more difficult.

Esiste una verità scomoda che ogni investitore, prima o poi, è costretto a incontrare. È una verità matematica, ma anche profondamente psicologica. Riguarda la dinamica delle perdite nei mercati finanziari e il rapporto che ogni portafoglio, e ogni mente, intrattiene con esse. In un mondo in cui la comunicazione finanziaria è dominata da grafici che celebrano i guadagni e da storie che raccontano moltiplicazioni rapide del capitale, esiste una legge silenziosa e implacabile: quella delle grandi perdite.

Il principio che ne sta alla base è tanto semplice quanto controintuitivo. Quando un asset, un titolo o un intero portafoglio subisce una perdita, il guadagno necessario per recuperare quella stessa perdita non è simmetrico. Perdere il 10% e guadagnare il 10% non equivale a tornare al punto di partenza. Al contrario, il recupero è sempre più difficile man mano che la perdita iniziale aumenta. Questa asimmetria, visivamente ben rappresentata nel grafico noto come «Law of Large Losses», è un fondamento matematico che ogni investitore dovrebbe interiorizzare prima ancora di pensare alla performance.

Nel grafico che accompagna queste riflessioni, vediamo una serie di traiettorie che si sviluppano a partire da diverse perdite iniziali. Per una contrazione del 10%, il rimbalzo necessario per riportarsi al livello iniziale è di poco superiore all’11%. Ma se la perdita diventa del 50%, il guadagno richiesto per tornare in pari raddoppia: 100%. E se il capitale si riduce del 60%, la ripresa dovrà essere del 150% per ritornare al punto di equilibrio. L’interesse composto, ma al contrario.

Il messaggio, dunque, non è solo matematico: è esistenziale. Man mano che si cade, risalire diventa esponenzialmente più difficile.

The law behind the numbers

The reason for this disparity is linked to the behavior of money in relative percentages. An investment of one hundred that loses 50% is worth fifty. To recover and return to one hundred, remaining capital will have to double. Therefore, it is not necessary to earn another 50%, but one hundred. The mistake many people make is to think in linear terms, when in fact markets operate on a geometric basis. This is where intuitive perception gives way to a reality that is more difficult to accept.

But the law of large losses is not just a matter of numbers: it is, first and foremost, a psychological event

When you suffer a significant loss, it is not simply an accounting decline. It causes an inner fracture. Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner in economics and father of «Behavioral Finance» (which I discussed in a recent article with the same title at this link), has shown that losses generate twice the emotional impact of equivalent gains. For an investor, losing ten thousand euros causes twice as much pain as the pleasure they would feel from earning the same amount. This emotional asymmetry is rooted in our evolution and is what drives many traders to make systematic mistakes at the very moment when clarity is most needed.

After a significant loss, the most common temptation is to want to get back in immediately, often with greater exposure, in an «attempt to make up for it». This is the classic trap of casino behavior: increasing the stakes to recover what has been lost, which in technical jargon is called martingale, or averaging in the context of trading. But in the markets, this logic is poisonous: increasing risk after a loss often means facing a second and more serious fall. And that is how large losses turn into permanent losses.

In addition, financial loss also has a corrosive effect on the investor's memory. Those who have experienced a major crash tend to become more risk-averse, distrustful of subsequent rises, and reduce their exposure even when the environment is favorable. In other words, the experience of a major loss structurally changes future behavior. It is not uncommon to encounter investors who, after a crisis, decide never to return to the markets, even at the cost of giving up important opportunities. The scar is deeper than the initial wound.

La legge dietro i numeri

La ragione di questa disparità è legata al comportamento del denaro in percentuali relative. Un investimento di cento che perde il 50% vale cinquanta. Per recuperare e tornare a cento, il capitale residuo dovrà raddoppiare. Non serve quindi guadagnare un altro 50%, ma cento. L’errore che molti commettono è di pensare in termini lineari, quando invece i mercati operano su base geometrica. È qui che la percezione intuitiva cede il passo alla realtà più difficile da accettare.

Ma la legge delle grandi perdite non è solo un affare di numeri: è, prima di tutto, un evento psicologico

Quando si subisce una perdita rilevante, non si registra semplicemente una flessione contabile. Si verifica una frattura interiore. Daniel Kahneman, premio Nobel per l’economia e padre della «Finanza Comportamentale» (di cui ho parlato in un recente articolo dal medesimo titolo a questo link), ha dimostrato che le perdite generano un impatto emotivo doppio rispetto ai guadagni equivalenti. Per un investitore, perdere diecimila euro produce un dolore che è due volte più intenso rispetto al piacere che proverebbe guadagnandone altrettanti. Questa asimmetria emotiva è radicata nella nostra evoluzione ed è ciò che spinge molti operatori a compiere errori sistematici proprio nel momento in cui la lucidità sarebbe più necessaria.

Dopo una perdita significativa, la tentazione più comune è quella di voler rientrare subito, spesso con maggiore esposizione, nel «tentativo di rifarsi». È la classica trappola del comportamento da casinò: aumentare la posta per recuperare quanto si è perso, quello che in gergo tecnico viene definita martingala, oppure mediazione se si parla nel contesto trading. Ma nei mercati appunto, questa logica è velenosa: aumentare il rischio dopo una perdita significa spesso andare incontro a una seconda e più grave caduta. Ed è così che le grandi perdite si trasformano in perdite permanenti.

Inoltre, la perdita finanziaria ha anche un effetto corrosivo sulla memoria dell’investitore. Chi ha vissuto un crollo importante tende a diventare più avverso al rischio, a diffidare dei rialzi successivi, a ridurre la propria esposizione anche quando il contesto è favorevole. In altre parole, l’esperienza di una perdita importante modifica strutturalmente il comportamento futuro. Non è raro incontrare investitori che, dopo una crisi, decidono di non tornare più sui mercati, anche a costo di rinunciare a opportunità importanti. La cicatrice è più profonda della ferita iniziale.

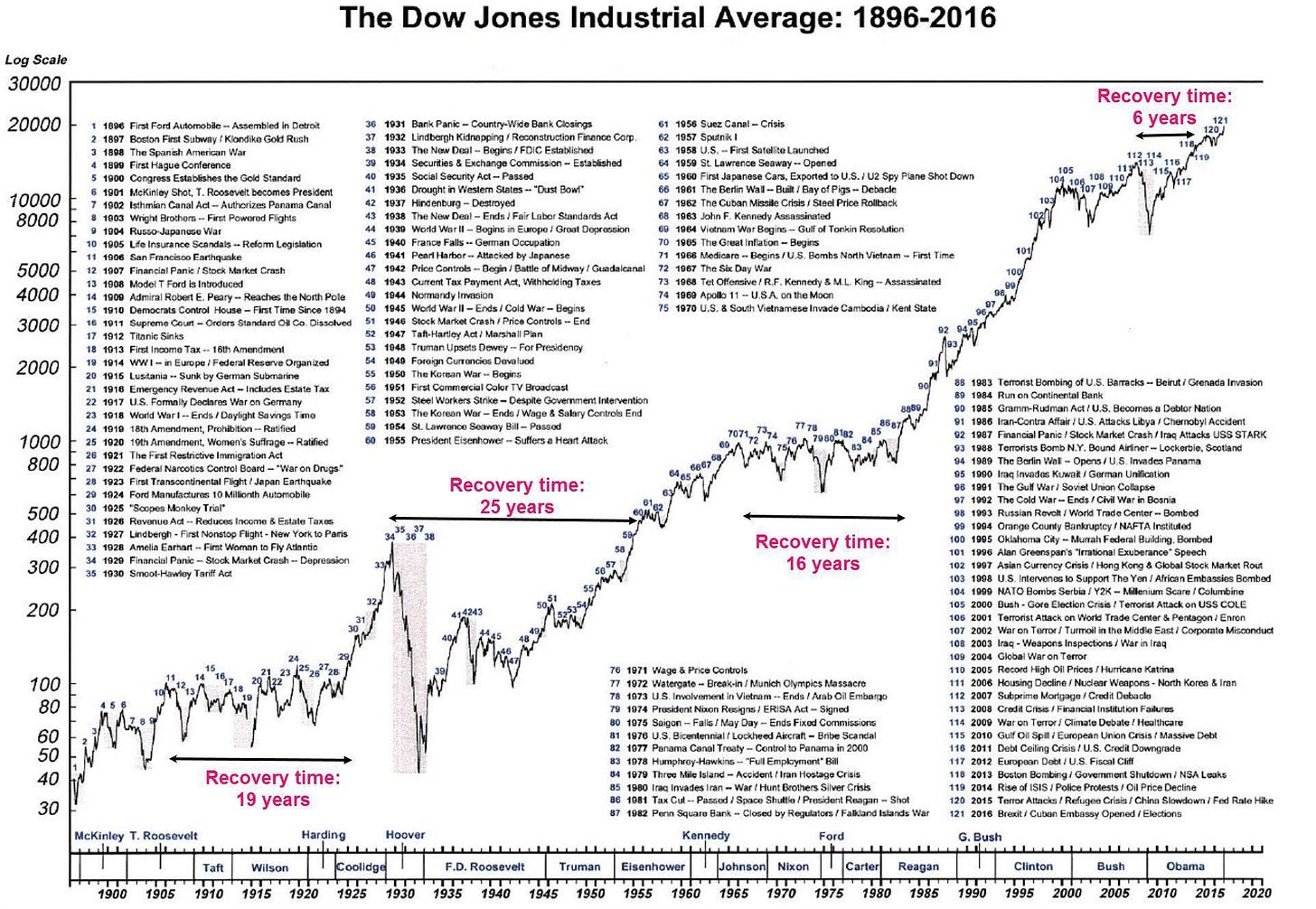

History and the past, shape and teach us

There are many historical examples that demonstrate how long and uncertain the road to recovery can be. After the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, Nasdaq lost over 70% of its value. It took more than fifteen years to return to previous levels. In the meantime, an entire generation of tech investors had already abandoned the field (be wary when you find topics such as «VWCE and chill» online, ed.). In 2022, Bitcoin suffered a collapse of more than 70% in just a few months. Although it subsequently showed signs of recovery, a significant proportion of retail investors sold at a loss, permanently burning any chance of recovery. These examples show the market can recover, but not all investors are able to follow it on its path and, above all, trends are real and objective, but the starting point is random and subjective.

In this context, the true skill of an investor lies not in the ability to predict rises, but in the ability to protect oneself from falls. Survival in the markets is more important than performance. Protecting capital, avoiding excessive drawdowns, limiting exposure in times of greatest uncertainty: these are the strategies that allow you to stay in the game and benefit from long-term growth. It is no coincidence that some of the best investors in history, from Warren Buffett to Paul Tudor Jones, Ray Dalio, and other Wall Street finance gurus, have always emphasized capital preservation over capital growth.

The mathematics of big losses, therefore, is not just a calculation, it is a guiding principle. It imposes mental and operational discipline. It teaches us that we cannot bet everything on the upside, because a single major negative event is enough to compromise years of work. It forces investors to think in terms of probabilities, scenarios, and the sustainability of their choices. Ultimately, the law of big losses forces us to take a dose of realism. It reminds us that greed has a price and risk, if underestimated, can become irreversible. It pushes us to abandon the illusion of easy gains and to build an investment philosophy based on prudence, patience, and awareness that time is an ally only for those who manage not to leave the game before the power of compound interest takes effect.

It is precisely this last point that closes the circle. Compounding, which is the true silent force of long-term growth, has one essential condition: continuity. But compounding cannot work if capital suffers a destructive loss. That is why the real victory in the markets is not to accumulate exceptional gains, but to avoid catastrophic losses. Those who manage to survive, remain calm in difficult times, and protect their capital during crashes will always have the opportunity to participate in subsequent rallies. Those who give in, on the other hand, risk being expelled from the system just when real opportunities are emerging.

The law of big losses is not a pessimistic theory. On the contrary, it is a guide to building resilient portfolios and clear minds. In this context, a qualified financial advisor can provide you with practical assistance in protecting your capital. It is a law that rewards those who know how to lose little, because in the long run, those who lose less win more.

La storia e gli eventi del passato ci segnano e insegnano

Esistono numerosi esempi storici che dimostrano quanto sia lunga e incerta la strada del recupero. Il Nasdaq, dopo lo scoppio della bolla dot-com nel 2000, perse oltre il 70% del suo valore. Per tornare ai livelli precedenti, impiegò più di quindici anni. Nel frattempo, un’intera generazione di investitori tecnologici aveva già abbandonato il campo (diffidate quando in rete trovate argomenti del tipo «VWCE and chill», ndr) Nel 2022, il Bitcoin ha subito un crollo superiore al 70% in pochi mesi. Anche se successivamente ha mostrato segnali di ripresa, una parte significativa degli investitori retail ha venduto in perdita, bruciando definitivamente la possibilità di recupero. Questi esempi dimostrano che il mercato può anche recuperare, ma non tutti gli investitori riescono a seguirlo nel percorso e soprattutto, che le tendenze sono reali e oggettive ma il punto di partenza è casuale e soggettivo.

In questo contesto, la vera competenza di un investitore non risiede nella capacità di prevedere i rialzi, ma in quella di proteggersi dalle cadute. La sopravvivenza, nei mercati, è più importante della performance. Proteggere il capitale, evitare drawdown eccessivi, limitare l’esposizione nei momenti di maggiore incertezza: queste sono le strategie che permettono di rimanere nel gioco e beneficiare della crescita nel lungo periodo. Non a caso, alcuni dei migliori investitori della storia, da Warren Buffett a Paul Tudor Jones, passando per Ray Dalio e altri guru della finanza di Wall Street, hanno sempre posto l’accento sulla conservazione del capitale prima ancora che sulla sua crescita.

La matematica delle grandi perdite, quindi, non è solo un calcolo, è un principio guida. Impone una disciplina mentale e operativa. Insegna che non si può puntare tutto sul rialzo, perché basta un singolo evento negativo di grande entità per compromettere anni di lavoro. Costringe l’investitore a pensare in termini di probabilità, di scenari, di sostenibilità delle proprie scelte. In ultima analisi, la legge delle grandi perdite ci costringe a un bagno di realismo. Ci ricorda che l’avidità ha un prezzo e che il rischio, se sottovalutato, può diventare irreversibile. Ci spinge ad abbandonare l’illusione del guadagno facile e a costruire una filosofia di investimento fondata sulla prudenza, sulla pazienza e sulla consapevolezza che il tempo è un alleato solo per chi riesce a non uscire dal gioco prima che agisca il potere dell’interesse composto.

È proprio quest’ultimo punto che chiude il cerchio. Il compounding, che è la vera forza silenziosa della crescita nel lungo termine, ha una condizione imprescindibile: la continuità. Ma il compounding non può operare se il capitale subisce una perdita distruttiva. È per questo che la vera vittoria nei mercati non è accumulare guadagni eccezionali, ma evitare perdite catastrofiche. Chi riesce a sopravvivere, a rimanere calmo nei momenti difficili e a proteggere il proprio capitale nei crolli, avrà sempre la possibilità di partecipare ai successivi rialzi. Chi invece cede, rischia di essere espulso dal sistema proprio nel momento in cui si preparano le vere opportunità.

La legge delle grandi perdite non è una teoria pessimista. È, al contrario, una guida per costruire portafogli resilienti e menti lucide. In questo contesto, un consulente finanziario competente può darti una mano concreta nella protezione del capitale. È una legge che premia chi sa perdere poco, perché nel lungo periodo, chi perde meno vince di più.

Anyone who has ever made a buy order on the market has noticed this law. Scars on the skin...