Make Sense to Buy at All-Time High?

What to do when trends are real and objective but the starting point is random and subjective?

Every time the markets reach a new all-time high, debate reignites with almost mathematical precision: does it make sense to enter now? Aren't we risking buying too high? Wouldn't it be better to wait for the next correction, the next reversal, the next signal tells us more clearly when market will offer a more favorable entry point?

This question, as simple as it is fascinating, has always been part of the history of finance, and is one of the most recurring topics in conversations between investors, financial advisors, savers, and commentators. Truth is that the very idea of an all-time high carries with it enormous emotional and psychological weight: on the one hand, feeling of having missed an opportunity, and on the other, fear of being the last to jump on the bandwagon, destined to be crushed when it derails. It is a dualism has been repeated throughout history and will continue to recur, because it touches on deep-seated aspects of human behavior: greed and fear, the desire to participate and fear of missing out.

To truly understand whether it makes sense to enter the market at its peak, we need to look beyond the present moment and broaden our perspective. History teaches us that historical highs are never a point of arrival, but simply an intermediate stage in a journey that, in the long term, tends to push ever higher. For example, anyone who asked themselves this question in 1985, watching the S&P500 hit 200 points for the first time, would probably have felt the same perplexity that many feel today. Yet that historic high was followed by others, and then by others still, until it reached over 6,500 points today. The same is true for the Dow Jones, which stood at 1,000 in 1982 and now stands at over 45,000: each high was perceived as an insurmountable limit, and each time it was surpassed, sometimes after painful corrections, other times with a more linear progression.

Ogni volta che i mercati raggiungono un nuovo massimo storico, il dibattito si riaccende con una puntualità quasi matematica: ha senso entrare adesso? Non rischiamo di acquistare troppo caro? Non sarebbe meglio attendere la prossima correzione, il prossimo storno, il prossimo segnale che ci dica con maggiore chiarezza quando il mercato offrirà un punto di ingresso più favorevole?

La domanda, tanto semplice quanto affascinante, accompagna da sempre la storia della finanza, ed è una delle più ricorrenti nelle conversazioni tra investitori, consulenti finanziari, risparmiatori e commentatori. La verità è che l’idea stessa di massimo storico porta con sé una carica emotiva e psicologica enorme: da un lato la sensazione di aver perso un’occasione, dall’altro la paura di essere gli ultimi a salire sul treno, destinati a rimanere schiacciati quando questo deraglierà. È un dualismo che si è ripetuto in ogni epoca e che continuerà a riproporsi, perché tocca corde profonde del comportamento umano: l’avidità e il timore, il desiderio di partecipare e la paura di restare fuori.

Per comprendere davvero se ha senso entrare a mercato sui massimi, bisogna guardare oltre l’istante presente e allargare la prospettiva. La storia ci insegna che i massimi storici non sono mai un punto di arrivo, ma semplicemente una tappa intermedia di un percorso che, nel lungo termine, tende a spingersi sempre più in alto. Chi, ad esempio, si fosse posto questa domanda nel 1985, osservando l’S&P500 toccare i 200 punti per la prima volta, avrebbe probabilmente provato le stesse perplessità che molti provano oggi. Eppure, quel massimo storico è stato seguito da altri, e poi da altri ancora, fino agli oltre 6500 punti di oggi. Lo stesso discorso vale per il Dow Jones, che nel 1982 si trovava a quota 1.000 e che oggi naviga oltre i 45.000: ogni massimo era percepito come un limite invalicabile, e ogni volta è stato superato, a volte dopo correzioni dolorose, altre volte con una progressione più lineare.

The «Value Creation» concept

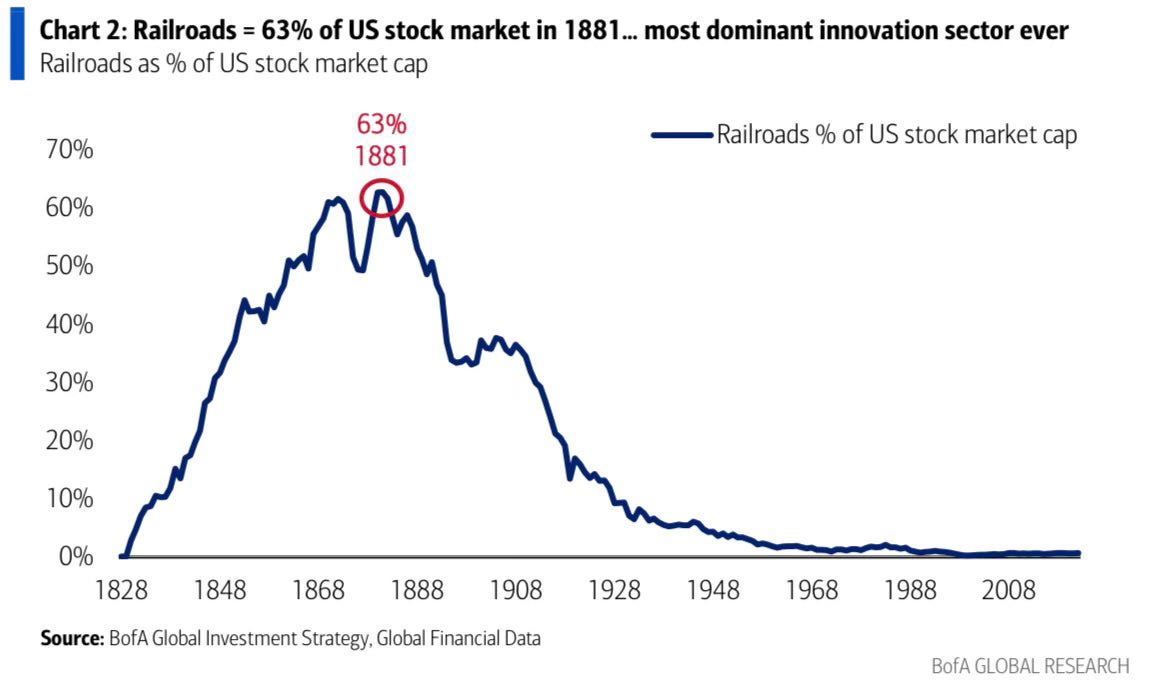

What is often overlooked is that historical highs are not an anomaly, but rather the natural condition of growing stock markets. A stock index represents the performance of the leading listed companies, which, as a whole, generate profits tend to increase over time, driven by innovation, productivity, and global economic growth. In reality, there are also other reasons for rebalancing of the stocks that make up the indices, with rather bizarre replacement rules (out with the bad apples, in with the new ones), but that's how it is.

Historical highs, therefore, reflect a process of value creation that accumulates year after year. Each new record is nothing more than the numerical translation of decades of technological progress, commercial expansion, globalization, organizational improvements, and new scientific discoveries. Think of the advent of internet, the spread of smartphones, revolutions in healthcare, logistics and artificial intelligence: each of these innovations has generated new markets, new opportunities and new profits, which have translated into market capitalization. Therefore, fearing the all-time high as if it were an end point is like watching a marathon at the ten-kilometer mark and thinking you can't go any further.

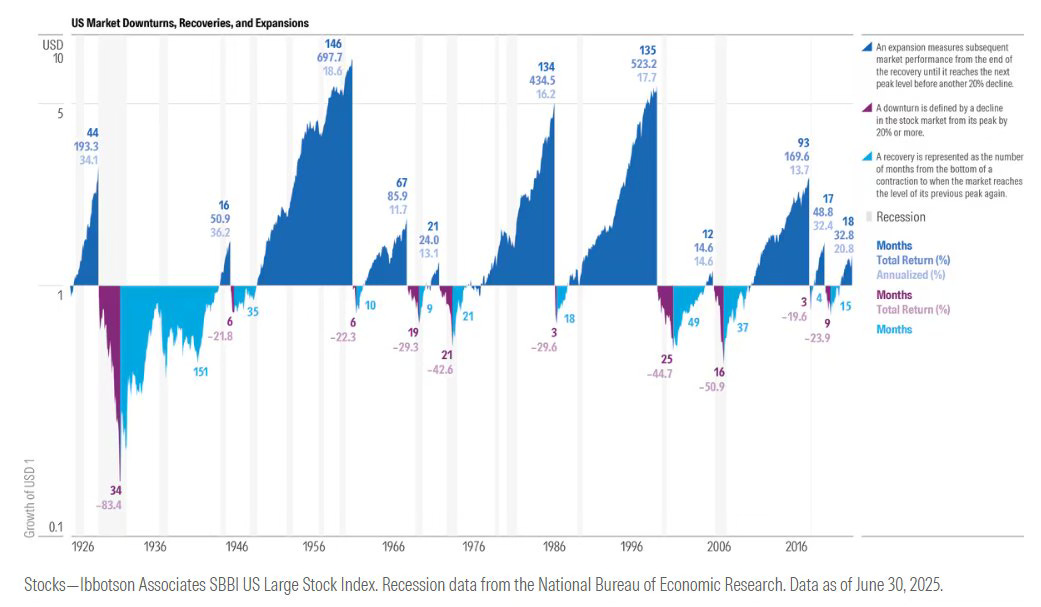

Of course, this doesn’t mean the market always rises in a linear fashion. On the contrary, the road to new highs is dotted with sudden declines, crises, and moments when it seems that everything is collapsing. In 2000, with the bursting of the dot-com bubble, S&P500 lost almost 50% of its value; in 2008, with the global financial crisis, the drawdown was even greater (Does anyone remember 666, the number of the beast, from March 9, 2009?). Yet those who had the patience and courage to remain invested, or to enter gradually, saw the market recover and exceed previous levels, setting new records. In hindsight, every all-time high has proved to be an acceptable entry point, provided you have a sufficiently long time horizon. This is where the difference between speculation and investment comes into play: speculation looks at the moment, the next week, next month, while investment looks at years and decades. For the long-term investor, today's all-time high will be tomorrow's all-time low.

Il concetto di «creazione di valore»

Ciò che spesso sfugge è che i massimi storici non sono un’anomalia, bensì la condizione naturale dei mercati azionari in crescita. Un indice azionario rappresenta l’andamento delle principali società quotate, e queste, nel complesso, producono utili che tendono ad aumentare nel tempo, spinti dall’innovazione, dalla produttività e dalla crescita economica globale. In realtà ci sono anche altre logiche di riassestamento tra i titoli che compongono gli indici, con regole di sostituzione alquanto bizzarre (fuori le mele marce, dentro quelle nuove) ma tant’è.

I massimi storici, dunque, sono il riflesso di un processo di creazione di valore che si accumula anno dopo anno. Ogni nuovo record non è che la traduzione numerica di decenni di progresso tecnologico, espansione commerciale, globalizzazione, miglioramenti organizzativi, nuove scoperte scientifiche. Pensiamo all’avvento di internet, alla diffusione degli smartphone, alle rivoluzioni nel campo della sanità, della logistica, dell’intelligenza artificiale: ciascuna di queste innovazioni ha generato nuovi mercati, nuove opportunità e nuovi utili, che si sono tradotti in capitalizzazione di borsa. Dunque, temere il massimo storico come se fosse un punto finale è come guardare una maratona al chilometro dieci e pensare che non si possa andare oltre.

Naturalmente, tutto questo non significa che il mercato salga sempre in modo lineare. Anzi, la strada verso nuovi massimi è costellata di discese improvvise, di crisi, di momenti in cui sembra che tutto stia crollando. Nel 2000, con lo scoppio della bolla dot-com, l’S&P500 perse quasi il 50% del suo valore; nel 2008, con la crisi finanziaria globale, il drawdown fu addirittura superiore (qualcuno ricorda 666, il numero della bestia del 9 Marzo 2009?). Eppure, chi ebbe la pazienza e il coraggio di restare investito, o di entrare gradualmente, ha visto il mercato recuperare e superare i livelli precedenti, stabilendo nuovi record. Ogni massimo storico, col senno di poi, si è rivelato un punto d’ingresso accettabile, a patto di avere un orizzonte temporale sufficientemente lungo. È qui che entra in gioco la differenza tra speculazione e investimento: la speculazione guarda all’istante, alla prossima settimana, al prossimo mese, mentre l’investimento guarda agli anni e ai decenni. Per l’investitore di lungo periodo, il massimo storico di oggi sarà il minimo storico di domani.

If everything is already priced in, you have to be in

One of the most enlightening anecdotes in this regard concerns Warren Buffett. Several times in his career, he was asked whether it made sense to buy when the markets had already risen significantly. His answer was always disarmingly simple: «The best time to invest was yesterday. The second-best time is today». This statement, which may seem trivial to many, actually contains a great truth: markets reward patience and time, not timing. Attempting to guess the exact point of bottom or top has historically proved to be a futile exercise. Studies show that missing even the ten best days of gains in a decade can drastically compromise the overall performance of a portfolio. And it is precisely in periods of great uncertainty, when markets seem to have already run too far, the most significant accelerations often occur.

Investor psychology, however, is much more complex than arithmetic logic. That’s why investor returns are always lower than those of the Index (I discussed this in a recent article entitled «The Product is You», where I published a study by DALBAR, ed.). Historical highs are frightening because they confront us with the ancestral fear of buying at the peak. It is a fear that feeds on past experiences, stories, and crises experienced firsthand. Those who lived through 2008 still have vivid memories of the collapse of Lehman Brothers, those who lived through 2000 remember well the collapse of technology stocks and those who witnessed the European debt crisis are well aware of the specter of the Euro's disintegration. These emotional scars influence today's choices, prompting many to postpone, wait, and believe it ‘s always too late. However, if we look at data, we find that markets spend a significant portion of their time near historic highs: if we systematically avoided them, we would remain on the sidelines for long periods, foregoing returns make a difference over time.

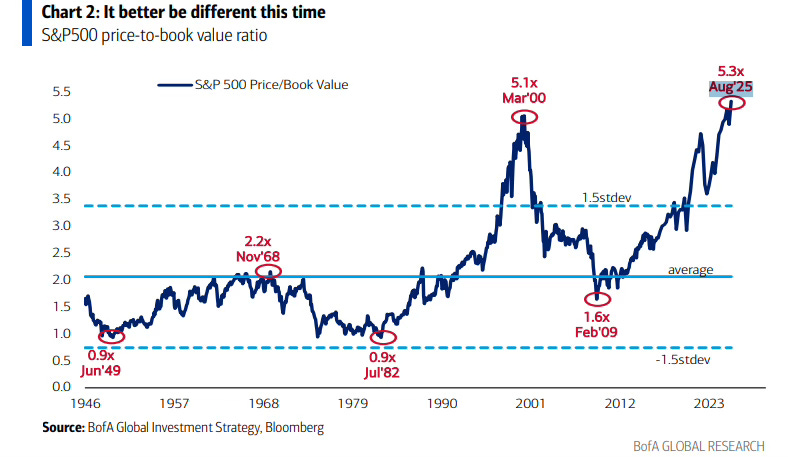

There is also another aspect that is often overlooked. When a market reaches new highs, it means investors have incorporated not only current corporate results into their valuations, but also expectations of future growth. The all-time high, therefore, is also a sign of collective confidence. Of course, sometimes this confidence can turn into irrational euphoria, as happened during the dot-com bubble or in the cryptocurrency period of 2017, but in most cases it is simply an indication the global economy continues to produce value and listed companies continue to benefit from this dynamic. Thinking that you can always identify the line between justified confidence and speculative euphoria is illusory: it is much more realistic to build diversified portfolios with time horizons consistent with your goals than to try to chase or anticipate highs.

Se è già tutto prezzato, tu devi essere dentro

Uno degli aneddoti più illuminanti a questo proposito riguarda Warren Buffett. Più volte nella sua carriera gli è stato chiesto se avesse senso comprare quando i mercati erano già saliti molto. La sua risposta è sempre stata disarmante nella sua semplicità: «Il momento migliore per investire era ieri. Il secondo momento migliore è oggi». Questa frase, che a molti può sembrare banale, racchiude in realtà una grande verità: i mercati premiano la pazienza e il tempo, non il tempismo. Il tentativo di indovinare il punto esatto di minimo o di massimo si è rivelato, storicamente, un esercizio sterile. Gli studi mostrano che perdere anche solo i dieci migliori giorni di rialzo in un decennio può compromettere drasticamente la performance complessiva di un portafoglio. Ed è proprio nei periodi di grande incertezza, quando i mercati sembrano già aver corso troppo, che spesso si verificano le accelerazioni più significative.

La psicologia dell’investitore, tuttavia, è molto più complessa della logica aritmetica. Ecco perché i rendimenti degli investitori sono sempre inferiori rispetto a quelli dell’Indice (ne ho parlato in un recente articolo «Il prodotto sei Tu» dove ho pubblicato uno studio di DALBAR, ndr). I massimi storici fanno paura perché ci mettono di fronte al timore ancestrale di comprare sul picco. È una paura che si nutre di esperienze passate, di racconti, di crisi vissute sulla propria pelle. Chi ha attraversato il 2008 porta ancora impressa la memoria del crollo di Lehman Brothers, chi ha vissuto il 2000 ricorda bene i titoli tecnologici azzerati, chi ha assistito alla crisi del debito Europeo ha ben presente lo spettro della disgregazione dell’Euro. Queste cicatrici emotive influenzano le scelte di oggi, spingendo molti a rimandare, ad attendere, a credere che sia sempre troppo tardi. Ma se osserviamo i dati, scopriamo che i mercati passano una porzione significativa del loro tempo in prossimità di massimi storici: se li evitassimo sistematicamente, resteremmo fuori per lunghi periodi, rinunciando a rendimenti che nel tempo fanno la differenza.

C’è anche un altro aspetto spesso trascurato. Quando un mercato tocca nuovi massimi, significa che gli investitori hanno incorporato nelle valutazioni non solo i risultati attuali delle aziende, ma anche aspettative di crescita futura. Il massimo storico, dunque, è anche un segnale di fiducia collettiva. Certo, a volte questa fiducia può trasformarsi in euforia irrazionale, come accadde durante la bolla delle dot-com o nel periodo delle criptovalute del 2017, ma nella maggior parte dei casi è semplicemente l’indicazione che l’economia globale continua a produrre valore e che le aziende quotate continuano a beneficiare di questa dinamica. Pensare di poter individuare sempre il confine tra fiducia giustificata ed euforia speculativa è illusorio: è molto più realistico costruire portafogli diversificati, con orizzonti temporali coerenti con i propri obiettivi, piuttosto che tentare di inseguire o anticipare i massimi.

Today's all-time highs will be tomorrow's springboard

A concrete example of how the perception of highs can be misleading can be found in 2013, when the S&P500 exceeded its pre-crisis levels of 2007 for the first time. Many investors thought it was too late to enter, that the market had already risen too much from its lows in 2009. In reality, that high was only the beginning of a decade of extraordinary growth, which would see the index multiply in value. Those who sat on the sidelines for fear of buying too high missed the opportunity to ride one of the longest and most profitable bull markets in history.

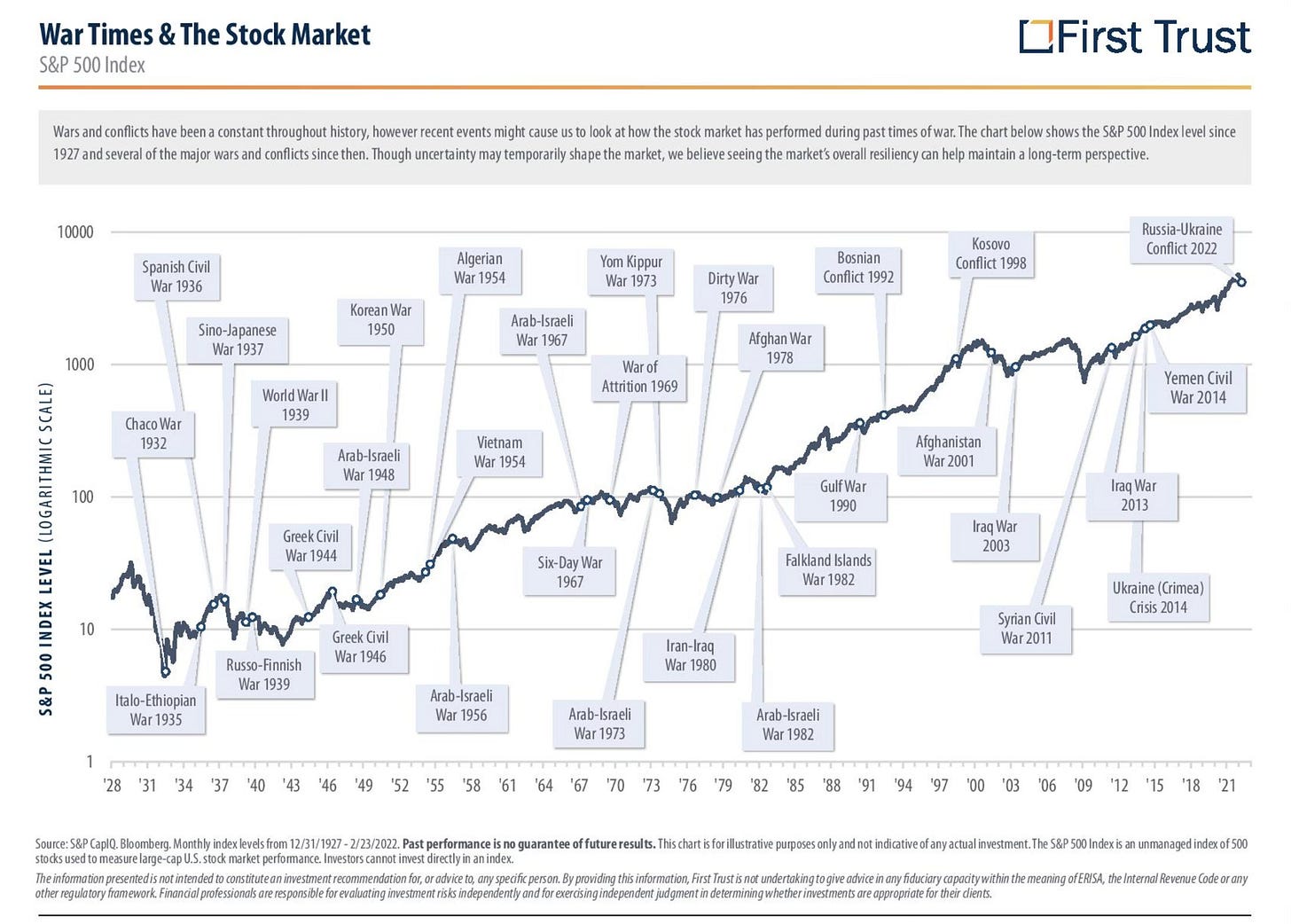

Ultimately, the question «does it make sense to enter at historic highs?» reveals more than it seems. It reveals the deeply human difficulty of accepting the future is uncertain and hope of identifying the perfect moment is actually an illusion. It reveals the tendency to seek confirmation in past crises and to underestimate the strength of long-term growth. Finally, it reveals the need to educate investors not to chase timing, but to build robust, consistent, and disciplined strategies. Historical highs are not alarm bells, but simply confirmation that market, as a whole, has been able to absorb shocks, crises, wars, pandemics, and innovations, while continuing to grow. Entering the market at such times, provided you have a long-term vision, is not a mistake, but a rational choice.

The real challenge, then, is not deciding whether or not to enter at the highs, but how to manage your emotions when you do. Because the market will inevitably offer moments of decline, and it will be in those moments your conviction that you have made the right choice will be put to the test. Investors who understand today's all-time highs are the springboard for tomorrow's highs will be able to remain calm during periods of volatility, transforming their initial doubts into a solid awareness: time, more than timing, is the markets' most faithful ally.

I massimi assoluti di oggi saranno il trampolino di domani

Un esempio concreto di come la percezione dei massimi possa essere ingannevole lo troviamo nel 2013, quando l’S&P500 superò per la prima volta i livelli pre-crisi del 2007. Molti investitori pensarono che fosse troppo tardi per entrare, che il mercato fosse già salito troppo rispetto ai minimi del 2009. In realtà, quel massimo fu solo l’inizio di un decennio di crescita straordinaria, che avrebbe portato l’indice a moltiplicare il proprio valore. Chi rimase alla finestra per paura di comprare troppo in alto perse l’opportunità di cavalcare uno dei mercati toro più lunghi e profittevoli della storia.

In definitiva, la domanda «ha senso entrare sui massimi storici?» rivela più di quanto sembri. Rivela la difficoltà, profondamente umana, di accettare che il futuro sia incerto e che la speranza di individuare il momento perfetto sia in realtà un’illusione. Rivela la tendenza a cercare conferme nelle crisi passate e a sottovalutare la forza della crescita di lungo periodo. Rivela, infine, la necessità di educare gli investitori non a rincorrere il tempismo, ma a costruire strategie robuste, coerenti e disciplinate. I massimi storici non sono campanelli d’allarme, ma semplicemente la conferma che il mercato, nel complesso, ha saputo assorbire shock, crisi, guerre, pandemie e innovazioni, continuando a crescere. Entrare a mercato in quei momenti, a patto di avere una visione di lungo termine, non è un errore, ma una scelta razionale.

La vera sfida, allora, non è decidere se entrare o meno sui massimi, ma come gestire la propria emotività quando lo si fa. Perché il mercato, inevitabilmente, offrirà anche momenti di ribasso, e sarà in quei momenti che la convinzione di aver fatto la scelta giusta verrà messa alla prova. L’investitore che avrà compreso che ogni massimo di oggi è il trampolino di lancio per i massimi di domani sarà quello capace di restare sereno nelle fasi di volatilità, trasformando il dubbio iniziale in una consapevolezza solida: il tempo, più del tempismo, è l’alleato più fedele dei mercati.