Why Europe Can Do It

Amid global challenges, wrong transitions, and new opportunities: why Europe remains fertile ground for the economy and investment

At a time when dominant narrative seems to want to relegate Europe to the role of spectator in the geopolitical duel between the United States and China, it is legitimate to ask whether the Old Continent still has something to say. Europe has made mistakes caused by dastardly political choices and a questionable ruling class, has shown rigidity, and often chased ideals rather than results. But it would be short-sighted to underestimate its resources because, despite everything, Europe can do it. And those who can look beyond immediate uncertainties can seize unique opportunities for investment, innovation and sustainable growth.

But before we go deeper, let's take a step back.

In un’epoca in cui la narrazione dominante sembra voler relegare l’Europa al ruolo di spettatrice del duello geopolitico tra Stati Uniti e Cina, è legittimo chiedersi se il Vecchio Continente abbia ancora qualcosa da dire. L’Europa ha commesso errori causati da scellerate scelte politiche e da una classe dirigente discutibile, ha mostrato rigidità, ha spesso inseguito ideali più che risultati. Ma sarebbe miope sottovalutarne le risorse perché, nonostante tutto, l’Europa può farcela. E chi saprà guardare oltre le incertezze immediate, potrà cogliere opportunità uniche d’investimento, innovazione e crescita sostenibile.

Ma prima di scendere in profondità, facciamo un passo indietro.

Inspiration from the American model

As early as the late 18th century, the birth of United States of America ignited the imagination of many European intellectuals. The principles of liberty and self-determination enshrined in the American Declaration of Independence inspired the French Revolution and ignited debate about how to refound European monarchies in a more modern sense. But it was in the twentieth century that American influence really exploded. After two world wars, with Europe in rubble, United States became a beacon, not only for economic reconstruction (Marshall Plan, ed.), but also for mass culture, labor organization, and lifestyle. Europe began to import not only material goods, but also ideological and cultural models: federalism, consumerism, cinema, music.

In the 1960s and 1970s, however, especially among young people, there was widespread criticism of the American model, which was accused of promoting a society that was materialistic, individualistic, and too tied to economic power. The rejection of the «American way of life» became a banner for protest movements, which though often imitated its communicative methods. Especially politically, European Union took inspiration from United States, for example in seeking greater integration between states, but always seeking its own way. European federalism remained unfinished, more complex and less centralized than the U.S. Today, in a multipolar world, Europe continues to look to the U.S. but with more careful and less naïve eyes. America remains a point of reference, for better or worse, in a transatlantic dialogue that, between convergences and divergences, continues to write history. But that is not all.

Ispirazione dal modello americano

Già a fine Settecento, la nascita degli Stati Uniti d’America accese la fantasia di molti intellettuali Europei. I principi di libertà e autodeterminazione sanciti nella Dichiarazione d’Indipendenza Americana ispirarono la Rivoluzione francese e accesero il dibattito su come rifondare le monarchie Europee in senso più moderno. Ma è nel Novecento che l’influenza americana esplose davvero. Dopo le due guerre mondiali, con l’Europa in macerie, gli Stati Uniti diventarono un faro, non solo per la ricostruzione economica (Piano Marshall, ndr), ma anche per la cultura di massa, l’organizzazione del lavoro, lo stile di vita. L’Europa cominciò a importare non solo beni materiali, ma anche modelli ideologici e culturali: il federalismo, il consumismo, il cinema, la musica.

Negli anni ’60 e ’70 però, soprattutto tra i giovani, si diffuse una critica al modello americano, accusato di promuovere una società materialista, individualista e troppo legata al potere economico. Il rifiuto dell’«American way of life» diventò una bandiera per i movimenti di protesta, che pur spesso ne imitarono i metodi comunicativi. Soprattutto sul piano politico, l’Unione Europea prese ispirazione dagli Stati Uniti, ad esempio nel cercare una maggiore integrazione tra Stati, ma sempre cercando una propria via. Il federalismo europeo è rimasto incompiuto, più complesso e meno centralizzato di quello americano: oggi, in un mondo multipolare, l’Europa continua a guardare agli Stati Uniti ma con occhi più attenti e meno ingenui. L’America resta un punto di riferimento, nel bene e nel male, in un dialogo transatlantico che, tra convergenze e divergenze, continua a scrivere la storia. Ma non è tutto.

The unresolved knots: bureaucracy and unbalanced transition

European Union was born not only as an economic project, but as a historical response to centuries (or even millennia if we look at world history, ed.) of devastation, including wars and divisions. From Treaty of Rome in the late 1960s to the birth of the Euro in 1999, via enlargement to the East and creation of the single market, Europe has built an unprecedented economic-political structure based on shared rules and interdependence. Indeed, it is not uncommon, flipping through the pages of European history, to come across times when the Old Continent has looked to the United States as a model to follow. From representative democracy to economic dynamism, via the myth of American dream, overseas influence has often left its mark on Europe's political, social and cultural choices.

However, this architecture has shown major cracks at times of crisis. The sovereign debt crisis of the past decade highlighted the lack of fiscal union and asymmetry of monetary policies with respect to the needs of individual states. Responses, often late and bureaucratized, undermined confidence in community mechanisms. At the same time, Europe has shown unexpected resilience, progressively strengthening instruments such as the ESM, banking supervision and, more recently, Recovery Fund. While it is true that Europe's strength lies in its multilevel governance and enforcement of rules, it is also true that system has produced an excess of bureaucracy, often unable to adapt to the speed of the contemporary economy. The sheer volume of regulations, rules and procedures, often poorly coordinated between Brussels and individual member states, has ended up hindering innovation, competitiveness and investment.

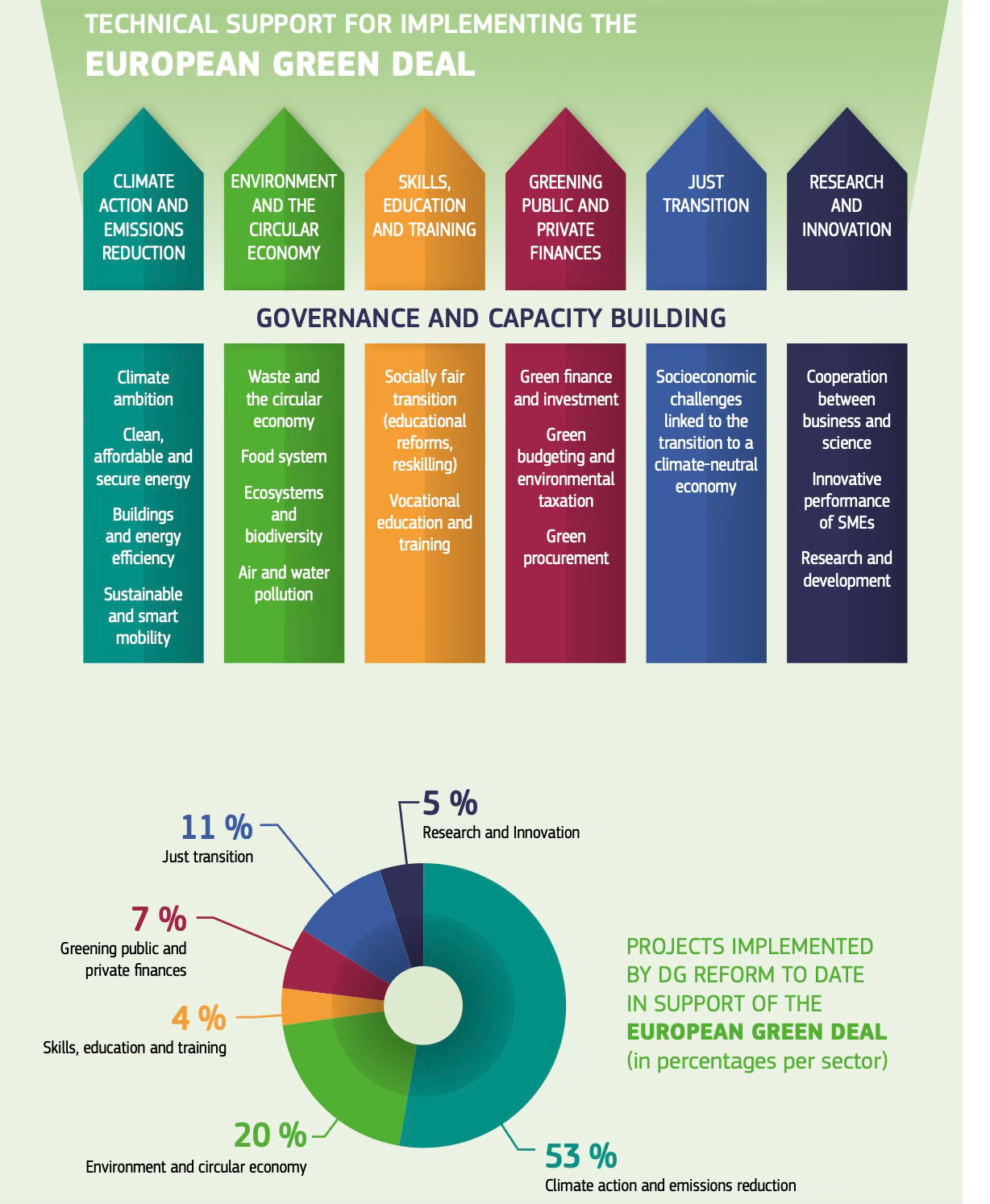

A case in point is the ecological transition. Driven by a righteous ambition but sometimes disconnected from industrial reality, European green strategy has imposed constraints and deadlines have put entire production sectors in difficulty, especially in the absence of an accompanying industrial strategy. The ban on endothermic engines from 2035, the «green homes» directive and absence of domestic raw materials are just some of the critical issues that show how transition was conceived more as an ethical imperative than a realistic path. The result? European companies fleeing to more permissive or better incentivized countries, such as United States or newly emerging ones in the East. A silent de-industrialization that risks undermining the continent's technological sovereignty, as well as social cohesion.

I nodi irrisolti: burocrazia e transizione sbilanciata

L’Unione Europea nasce non solo come progetto economico, ma come risposta storica a secoli (o addirittura millenni se guardiamo la storia del mondo, ndr) di devastazioni, tra guerre e divisioni. Dal Trattato di Roma della fine degli anni 60’ fino alla nascita dell’Euro nel 1999, passando per l’allargamento a Est e la creazione del mercato unico, l’Europa ha costruito una struttura economico-politica senza precedenti, fondata su regole condivise e interdipendenza. Non è raro infatti, sfogliando le pagine della storia europea, imbattersi in momenti in cui il Vecchio Continente ha guardato agli Stati Uniti come a un modello da seguire. Dalla democrazia rappresentativa al dinamismo economico, passando per il mito del sogno americano, l’influenza d’oltreoceano ha spesso lasciato un segno nelle scelte politiche, sociali e culturali dell’Europa.

Tuttavia, questa architettura ha mostrato crepe importanti nei momenti di crisi. La crisi del debito sovrano dello scorso decennio ha messo in luce la mancanza di un’unione fiscale e l’asimmetria delle politiche monetarie rispetto alle esigenze dei singoli Stati. Le risposte, spesso tardive e burocratizzate, hanno minato la fiducia nei meccanismi comunitari. Allo stesso tempo l’Europa ha dimostrato una capacità di tenuta inaspettata, rafforzando progressivamente strumenti come il MES, la supervisione bancaria e, più recentemente, il Recovery Fund. Se è vero che la forza dell’Europa risiede nella sua governance multilivello e nella tutela delle regole, è altrettanto vero che proprio questo sistema ha prodotto un eccesso di burocrazia, spesso incapace di adattarsi alla velocità dell’economia contemporanea. La mole di regolamenti, norme e procedure spesso poco coordinati tra Bruxelles e i singoli Stati membri, ha finito per ostacolare innovazione, competitività e investimenti.

Un esempio emblematico è rappresentato dalla transizione ecologica. Spinta da un’ambizione giusta ma talvolta scollegata dalla realtà industriale, la strategia green europea ha imposto vincoli e scadenze che hanno messo in difficoltà interi settori produttivi, soprattutto in assenza di una strategia industriale di accompagnamento. Il divieto sui motori endotermici dal 2035, la direttiva sulle «case green» e l’assenza di materie prime interne sono solo alcune delle criticità che mostrano come la transizione sia stata concepita più come un imperativo etico che come un percorso realistico. Il risultato? Aziende europee in fuga verso Paesi più permissivi o meglio incentivanti, come gli Stati Uniti o i nuovi emergenti ad Oriente. Una de-industrializzazione silenziosa che rischia di compromettere la sovranità tecnologica del continente, oltre alla coesione sociale.

The decade of choices: concrete opportunities

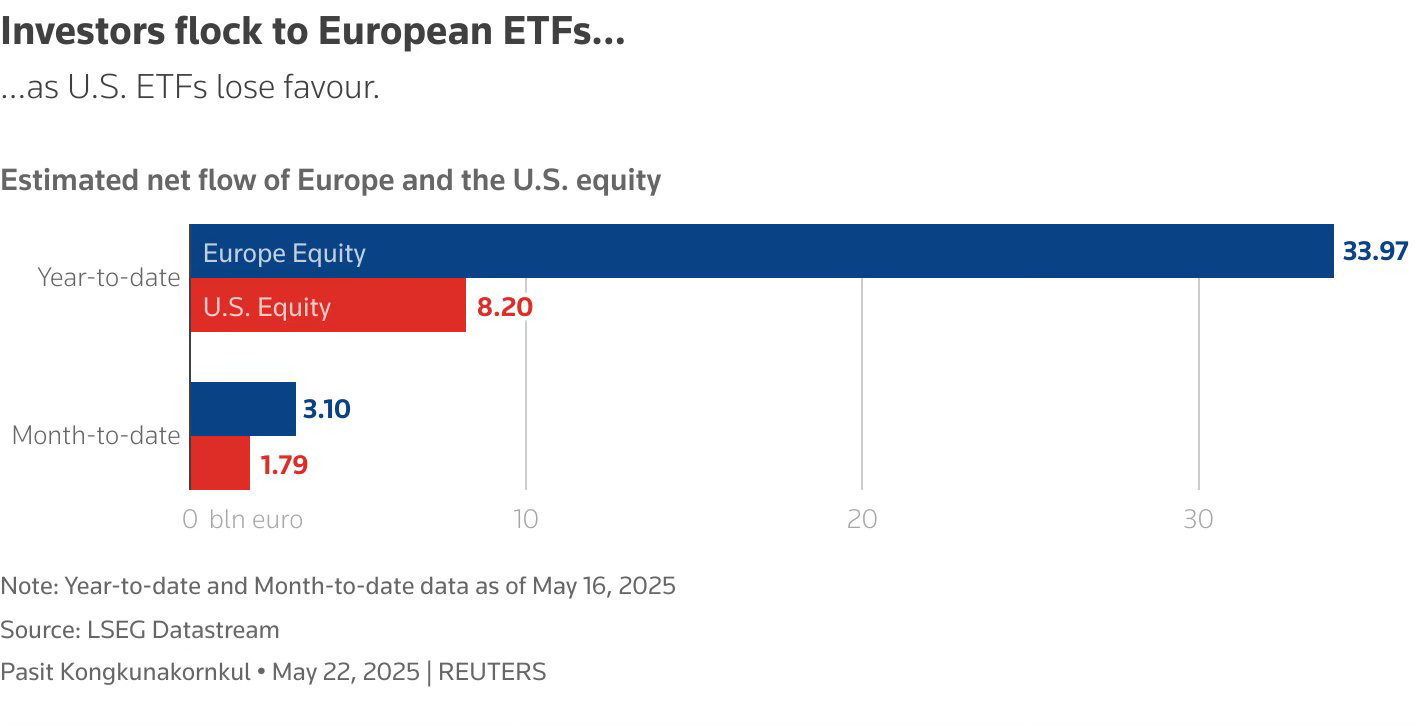

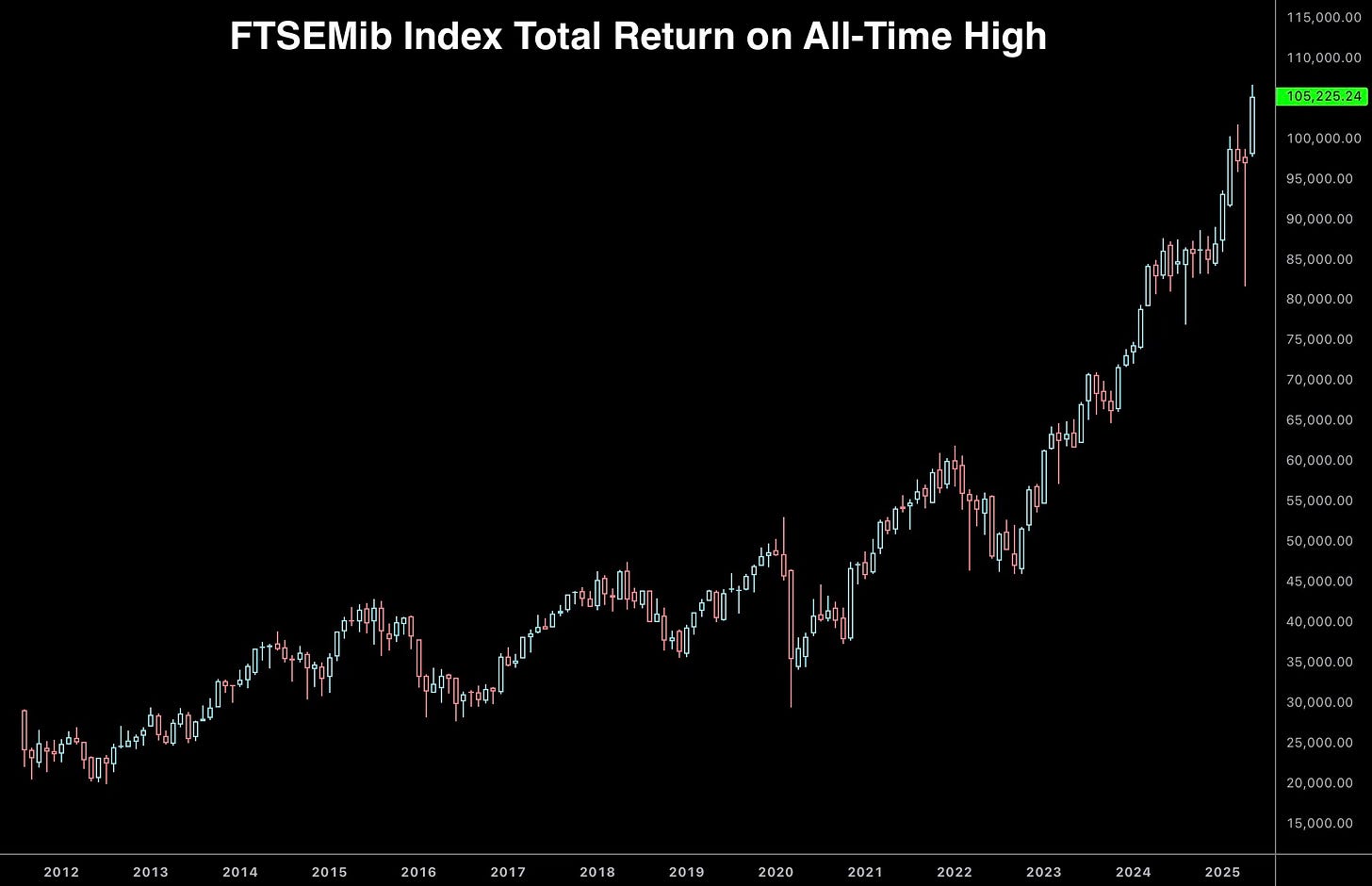

Despite critical issues, Europe retains a wealth of unparalleled value. Its human capital is among the most qualified in the world, thanks to strong education systems, excellent universities and cutting-edge scientific research. Logistics, energy and digital infrastructure, while uneven across member states, remains among the most advanced and secure. Moreover, compliance and quality of life make Europe fertile ground for patient, long-term investment. In an increasingly unstable world (especially politically, ed.), regulatory predictability, even if cumbersome, is a competitive advantage. European financial markets are somewhat undervalued compared to Wall Street, offering attractive growth margins for those who can select the right sectors/instruments.

Europe's future will depend on its ability to turn crises into strategic leverage. The pandemic, for example, has prompted EU to adopt the Next Generation EU, an extraordinary public investment plan that, if well managed, can bridge infrastructure and digital gaps in many member countries. The rehabilitation of production chains, partly a consequence of the pandemic and partly of growing Asian instability, may provide a unique opportunity to revitalize European industry, especially in less developed areas.

Europe's new strategic autonomy (especially after election of the Trump administration, ed.) is already a key issue in areas such as energy, defense, semiconductors, and cloud; the creation of European industrial alliances is showing a clear change of pace. Digitization, traditionally a weak point, is also receiving impetus with adoption of specific and direct plans: at the beginning of the new and inevitable era of Artificial Intelligence this can certainly be a decisive step, if excessive regulatory drifts are avoided.

Il decennio delle scelte: opportunità concrete

Al netto delle criticità, l’Europa conserva un patrimonio di valore ineguagliabile. Il capitale umano è tra i più qualificati al mondo, grazie a sistemi educativi solidi, università di eccellenza e una ricerca scientifica di punta. L’infrastruttura logistica, energetica e digitale, seppur disomogenea tra gli Stati membri, resta tra le più avanzate e sicure. Inoltre, il rispetto delle regole e la qualità della vita rendono l’Europa un terreno fertile per investimenti pazienti, a lungo termine. In un mondo sempre più instabile (specialmente dal punto di vista politico, ndr), la prevedibilità normativa anche se farraginosa, rappresenta un vantaggio competitivo. I mercati finanziari europei sono in parte sottovalutati rispetto ai corrispettivi statunitensi, offrendo margini di crescita interessanti per chi saprà selezionare i settori/strumenti giusti.

Il futuro dell’Europa dipenderà dalla capacità di trasformare le crisi in leva strategica. La pandemia, ad esempio, ha spinto l’UE ad adottare il Next Generation EU, un piano straordinario di investimenti pubblici che, se ben gestito, potrà colmare i gap infrastrutturali e digitali di molti Paesi membri. Il risanamento delle catene di produzione, in parte conseguenza della pandemia e in parte della crescente instabilità asiatica, potrà rappresentare un’occasione unica per rilanciare l’industria europea, soprattutto nelle aree meno sviluppate.

La nuova autonomia strategica europea (in particolare dopo l’elezione dell’amministrazione Trump, ndr) è già un tema chiave in settori come energia, difesa, semiconduttori e cloud; la creazione di alleanze industriali europee sta mostrando un cambio di passo evidente. Anche la digitalizzazione, tradizionalmente un punto debole, sta ricevendo impulso con l’adozione di piani specifici e diretti: all’inizio della nuova e inevitabile era dell’Intelligenza Artificiale questo potrà essere sicuramente un passo decisivo, qualora si evitino derive regolamentari eccessive.

Investing in Europe: yes or no?

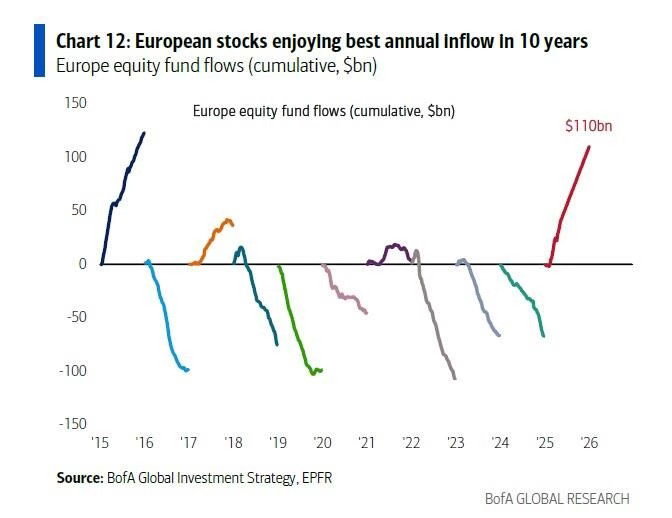

For an investor today, Europe represents a less spectacular but more solid bet. Equity multiples are lower than in the United States, leaving room for significant appreciation. European funds available for energy and digital transition represent unprecedented fiscal leverage. Sectors such as green, defense, digital health and deep-tech offer enormous scope for development. In addition, the increasing focus on ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance, ed.) criteria makes Europe a global reference, with stricter but also more credible standards. This means that many European companies will be better positioned in a world, ideological drifts aside, will face structural environmental and social transformations.

Europe has often missed opportunities for economic, technological and political leadership. It has succumbed to regulatory excesses, chased ideals without strategies, and neglected industry in the name of abstract sustainability. But it has also demonstrated, in its difficulties, a resilience few other systems can boast. Old World will never be a startup like those «made in the USA»: it is not young, it is not agile, it is not fast, but it is resilient, structured and, if reformed intelligently, still deeply competitive. That is why it can make it. Old is not synonymous with something to be thrown away, but to be cherished, protected, and enhanced, and those who decide to invest in it today, with vision and pragmatism, could find themselves among the protagonists of yet another European renaissance.

Investire in Europa: yes or no?

Per un investitore, l’Europa rappresenta oggi una scommessa meno spettacolare ma più solida. I multipli azionari sono più bassi rispetto agli Stati Uniti, lasciando spazio a rivalutazioni significative. I fondi Europei a disposizione per la transizione energetica e digitale rappresentano una leva fiscale senza precedenti. Settori come il green, la difesa, la sanità digitale e il deep-tech offrono margini di sviluppo enormi. Inoltre, l’attenzione sempre maggiore verso i criteri ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance, ndr) rende l’Europa un riferimento globale, con standard più severi ma anche più credibili. Questo significa che molte aziende europee saranno meglio posizionate in un mondo che, al netto delle derive ideologiche, dovrà affrontare trasformazioni ambientali e sociali strutturali.

L’Europa ha spesso perso occasioni per leadership economica, tecnologica e politica. Ha ceduto a eccessi regolatori, ha inseguito ideali senza strategie, ha trascurato l’industria in nome della sostenibilità astratta. Ma ha anche dimostrato, nelle difficoltà, una capacità di tenuta che pochi altri sistemi possono vantare. Il Vecchio Continente non sarà mai una startup come quelle «made in USA»: non è giovane, non è agile, non è veloce, ma è resiliente, strutturata e, se riformata con intelligenza, ancora profondamente competitiva. Per questo può farcela. Vecchio non è sinonimo di qualcosa da buttare, ma da custodire, proteggere e valorizzare e chi oggi decide di investirvi, con visione e pragmatismo, potrebbe trovarsi tra i protagonisti della prossima, ennesima, rinascita europea.