Where to Sell

Investors should always remain invested: let's find out when and how to sell in some crucial situations in life

For some time now, I’ve been expressing a series of unconventional opinions. Not because I like to provoke, but I believe in a world saturated with slogans and clichés, we need to stop every now and then and really think about how markets work, how we relate when dealing with money. And today I want to offer you a reflection, at first, may sound uncomfortable. What if I told you that, in your financial life, the balance you start with and balance you end up with will be more or less the same? Does it seem like a paradox?

Every day, we are invaded with the opposite message: invest, buy this product, follow this strategy, and you will find yourself with capital multiplied by 5, 10 or 100. But the reality is that, for most people, will not be the case. Because we are human, and as such, emotional and vulnerable. Throughout our lives, we are overwhelmed by a series of impulses: the advisor who offers us the latest «revolutionary» product, video teaches us how to get rich in three steps, trend of the moment that seems unstoppable. There is no malice whatsoever: problem is that choices are often made with the gut, not the head. And so it happens, despite the long-term historical growth trends of the markets, many people fail to benefit from them.

They sell in panic at the worst moments, buy when prices are already at their highest and constantly change strategy. Sometimes out of fear, sometimes out of greed

At the end of the day, result is disappointing: at best, you find yourself back where you started; at worst, you accumulate significant losses. And then people start talking badly about finance. But truth is that markets follow their own age-old logic; it is we who continually deviate from our initial intentions. If we want to change things, we have to change our perspective. Finance is not an ATM that dispenses wealth on demand. It is a tool, powerful and dangerous at the same time, can only work if we learn to respect it. So if there are no magic formulas, how can we protect ourselves? Well, the key word when talking about markets and finance in general should be protection. Here are some obvious examples:

a job that generates a stable cash flow: true financial security starts with income, not investments

an emergency fund: a reserve that allows us to deal with unexpected events without having to dismantle our investments at the wrong time

a basket of a few carefully selected, high-quality instruments held for the long term (and occasionally maintained), with the purpose-only of protecting purchasing power from inflation and, why not, generating some returns

It's not as exciting as a promise of returns. It's not as spectacular as stories on the front page, but it's truth for the majority of people.

Da qualche tempo porto avanti una serie di opinioni controcorrente. Non perché ami provocare, ma perché credo che in un mondo saturo di slogan e frasi fatte, serva ogni tanto fermarsi e ragionare davvero su come funzionano i mercati, su come funzioniamo noi quando ci rapportiamo al denaro. E oggi voglio proporvi una riflessione che, all’inizio, potrebbe suonare scomoda. Se vi dicessi che, nella vostra vita finanziaria, il saldo con cui partirete e quello con cui arriverete alla fine saranno, più o meno, gli stessi? Sembra un paradosso?

Siamo invasi ogni giorno dal messaggio opposto: investi, compra questo prodotto, segui questa strategia e ti troverai con un capitale moltiplicato per 5, per 10 o per 100. Ma la realtà è che, per la maggior parte delle persone, le cose non andranno così. Perché siamo umani, e in quanto tali, emotivi e vulnerabili. Nel corso della vita veniamo travolti da una serie di stimoli: il consulente che ci propone l’ultimo prodotto «rivoluzionario», il video che ci insegna come diventare ricchi in tre mosse, il trend del momento che sembra inarrestabile. Non c’è malafede in assoluto: il problema è che le scelte vengono spesso fatte di pancia, non di testa. E così accade che, nonostante i mercati nel lungo periodo abbiano tendenze storiche di crescita, molte persone non riescano a beneficiarne.

Vendono nel panico nei momenti peggiori, comprano quando i prezzi sono già ai massimi, cambiano continuamente strategia. A volte per paura, a volte per avidità

Alla fine del percorso, il risultato è deludente: nel migliore dei casi ci si ritrova al punto di partenza, nel peggiore si accumulano perdite importanti. E allora si parla male della finanza. Ma la verità è che i mercati seguono le loro logiche secolari, siamo noi a deviare continuamente dalle intenzioni iniziali. Se vogliamo cambiare le cose, dobbiamo cambiare prospettiva. La finanza non è un bancomat che ci eroga ricchezza a comando. È uno strumento, potente e pericoloso allo stesso tempo, che può funzionare solo se impariamo a rispettarlo. Quindi se non esistono formule magiche, come possiamo proteggerci? Ecco, la parola chiave quando si parla di mercati e finanza in generale dovrebbe essere protezione. Alcuni esempi banali:

un lavoro che generi un flusso di cassa stabile: la vera sicurezza finanziaria parte dal reddito, non dagli investimenti

un fondo di emergenza: una riserva che ci permetta di affrontare imprevisti senza dover smontare i nostri investimenti al momento sbagliato

un paniere di pochi strumenti di qualità, selezionati con cura e tenuti per il lungo periodo (manutenuti talvolta), con l’unico scopo di proteggere il potere d’acquisto dall’inflazione e perché no, qualche rendimento

Non è entusiasmante come una promessa di rendimenti. Non è spettacolare come le storie da copertina, ma è la verità per la stragrande maggioranza delle persone.

Where to sell, according to Peter Lynch

Having clarified that investing is a much more complex concept than it is often portrayed (investors in the literal sense of the term «should» always remain invested, ed.), there comes a time in life when the portfolio is dismantled. The reasons for this can vary greatly: need for liquidity, change in portfolio assets, restructuring, maintenance, fear, greed, and much more. At this point, the question arises: where to sell? Or rather, where to start when closing an investment?

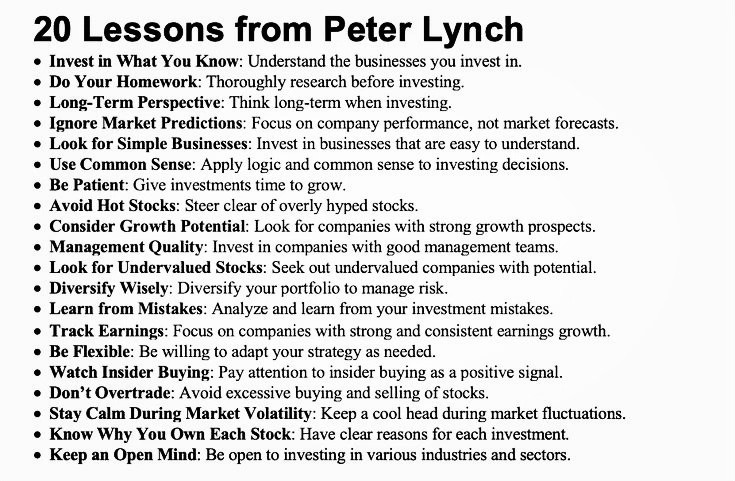

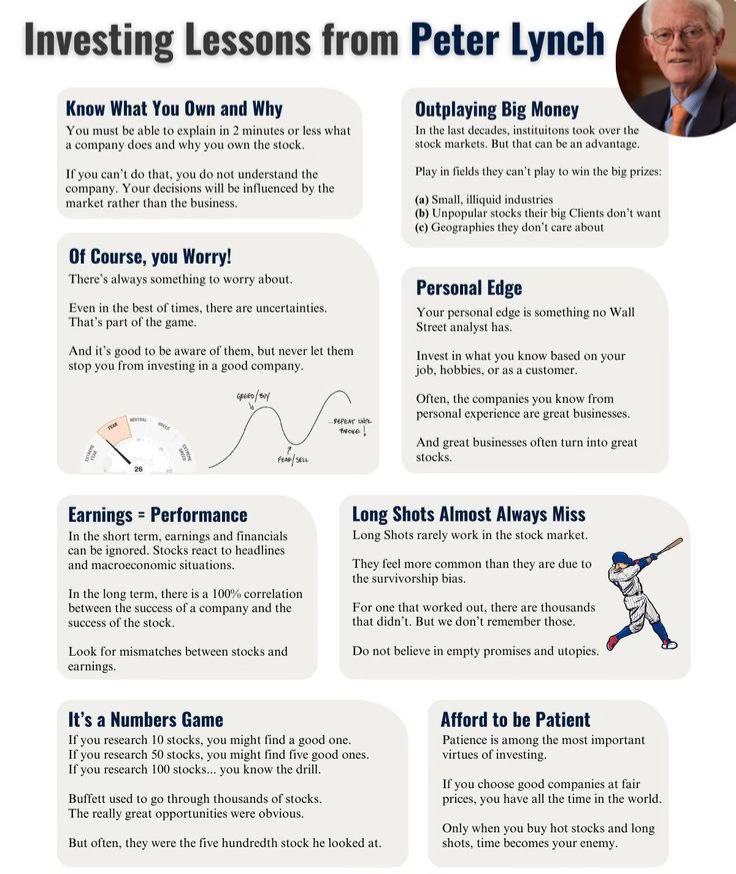

When it comes to selling, the most common mistake is to think there’s a right time applies to everyone. Truth is that there is no universal formula, nor is there a magic price level indicates the peak before the decline. The art of selling is, first and foremost, the art of understanding the story behind the stock we own and recognizing when that story has ceased to work.

Before delving into reflections on disinvestment, it is worth mentioning Peter Lynch, one of the most iconic figures in investment history. Manager of Fidelity's legendary Magellan fund between the late 1970s and early 1990s, Lynch achieved average annual returns of over 29%, transforming the fund from just over $20 million to over $14 billion. His philosophy, summarized in his famous book «One Up on Wall Street», is simple and revolutionary at the same time: invest in what you know, analyze companies thoroughly and have patience to let time do its work. But while Lynch is best remembered for his talent for finding winning stories, his reflections on when to sell are equally enlightening. These are not guru-like insights, but pragmatic criteria that always start from an analysis of fundamentals and consistency with our lives as investors.

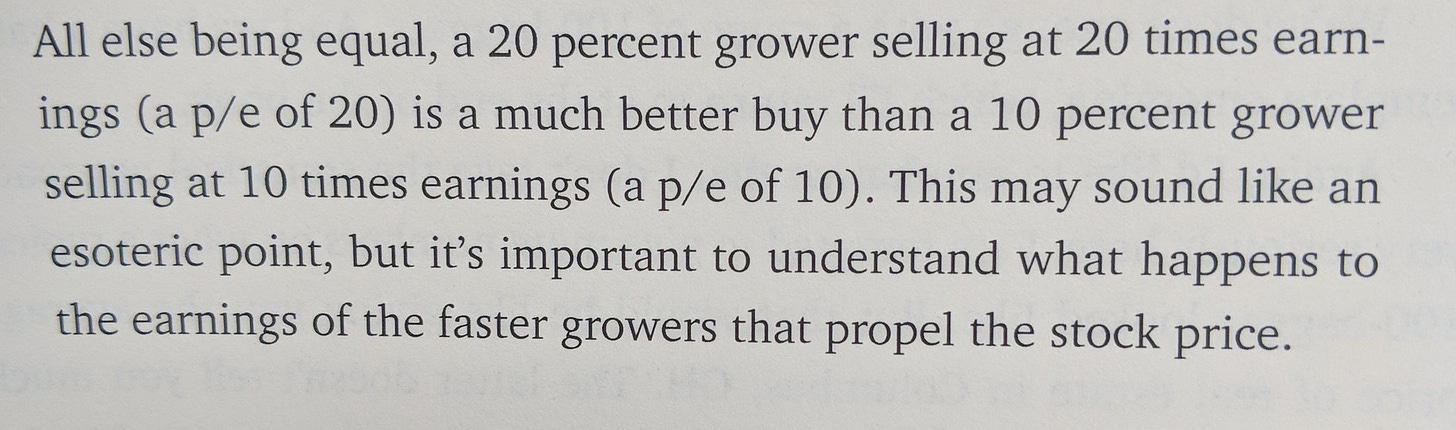

Lynch reiterates this very clearly: you should not sell out of boredom, fear, or because «it has risen too much» without a reason. You should sell when the reasons you bought are no longer valid or when the implicit risk has far exceeded the potential benefit. Take, for example, solid, mature companies, the so-called stalwarts (in technical jargon, these are established companies with a leading position in their sector and moderate but steady growth, ed.). These are often brands we know well, leaders in their sectors, with stable balance sheets and predictable cash flows. Here, the problem is not survival, but market's excessive enthusiasm. There have been famous cases in recent history where highly admired companies have reached stratospheric valuation multiples, only to retrace sharply once the reality of the numbers took over.

Those who bought tech stocks in 2021 that were already heavily priced on the basis of zero interest rates and infinite liquidity, without asking themselves whether the fundamentals justified such valuations, found themselves facing double-digit losses in the following two years. That’s why Lynch urges discipline: if P/E ratio is much higher than the historical average and there is no future growth to justify it, the risk of being trapped increases. In such cases, selling is a healthy profit-taking move, not a sign of weakness.

Dove vendere, secondo Peter Lynch

Chiarito che l’investimento è un concetto molto più complesso di come viene raccontato (l’investitore nel senso letterario del termine, «dovrebbe» rimanere sempre investito, ndr), arriva un momento durante la propria vita, in cui il portafoglio viene smontato. I motivi possono essere i più disparati: esigenza di liquidità, cambio degli asset in portafoglio, ristrutturazione, manutenzione, paura, avidità e molto altro ancora. A questo punto la domanda sorge spontanea: dove vendere? O meglio, da dove partire per chiudere un investimento?

Quando si parla di vendita, l’errore più comune è pensare che esista un momento giusto valido per tutti. La verità è che non esiste una formula universale, né un livello di prezzo magico che indichi la vetta massima prima di scendere. L’arte del vendere è, prima di tutto, l’arte di capire la storia che c’è dietro il titolo che possediamo e di riconoscere quando quella storia ha smesso di funzionare.

Prima di entrare nel merito delle riflessioni sul disinvestimento, vale la pena spendere due parole su Peter Lynch, una delle figure più iconiche della storia degli investimenti. Gestore del leggendario fondo Magellan di Fidelity tra la fine degli anni Settanta e i primi Novanta, Lynch ha realizzato rendimenti medi annui superiori al 29%, trasformando il fondo da poco più di 20 milioni a oltre 14 miliardi di dollari. La sua filosofia, riassunta nel celebre libro «One Up on Wall Street», è semplice e al tempo stesso rivoluzionaria: investire in ciò che si conosce, analizzare a fondo le aziende e avere la pazienza di lasciar lavorare il tempo. Ma se Lynch è ricordato soprattutto per il suo talento nel trovare storie vincenti, le sue riflessioni su quando vendere sono altrettanto illuminanti. Non si tratta di intuizioni da guru, ma di criteri pragmatici che partono sempre dall’analisi dei fondamentali e dalla coerenza con la nostra vita di investitori.

Lynch lo ribadisce con estrema chiarezza: non bisogna vendere per noia, paura o perché «è salito troppo» senza un motivo. Bisogna vendere quando i motivi per cui abbiamo comprato non sono più validi o quando il rischio implicito ha superato di molto il potenziale beneficio. Prendiamo ad esempio le aziende solide e mature, i cosiddetti stalwart (nel gergo tecnico sono società consolidate, con una posizione di leadership nel loro settore e una crescita moderata ma costante, ndr). Sono spesso marchi che conosciamo bene, leader nei loro settori, con bilanci stabili e flussi di cassa prevedibili. Qui il problema non è la sopravvivenza, ma l’eccesso di entusiasmo del mercato. Ci sono stati casi celebri nella storia recente in cui aziende molto ammirate hanno raggiunto multipli di valutazione stratosferici, per poi rintracciare bruscamente una volta che la realtà dei numeri ha ripreso il sopravvento.

Chi nel 2021 acquistava titoli tecnologici già ampiamente prezzati sulla base di tassi a zero e liquidità infinita, senza chiedersi se i fondamentali giustificassero simili valutazioni, si è trovato nei due anni successivi a fronteggiare perdite anche a doppia cifra. Ecco perché Lynch invita a essere disciplinati: se il rapporto Prezzo/Utili è molto più alto della media storica e non c’è una crescita futura che lo giustifichi, il rischio di restare intrappolati aumenta. La vendita, in questi casi, è una presa di profitto sana, non un segno di debolezza.

What and when to sell: cyclical vs. growth

In the case of cyclical companies, the discussion is even more fascinating. Here, it is not how much they earn today that matters, but where we are in the cycle. Steel, energy, semiconductors: sectors notoriously subject to fluctuations linked to the global economy. Lynch suggests looking for signs that often come before the financial statements: accelerating inflation, commodity prices changing direction, companies starting a price war to defend market share. These are all symptoms that peak of the cycle may be near. Those who invest in cyclical companies must accept an uncomfortable truth: you cannot hold them forever; you must have the courage to sell when market is euphoric and buy when it is depressed. This is the opposite of what our emotions tell us, but it is how you get the best results.

Even more insidious is the temptation to hold on to so-called growth stocks, fast-growing companies, indefinitely. These are the ones everyone talks about, the stocks end up on the covers of financial newspapers and generate real cult following. Here too, Lynch is clear: you must not fall in love with a stock. If the price already reflects unrealistic growth scenarios, if all analysts unanimously recommend it, and if margins are starting to shrink, then perhaps most of the potential has already been captured. History is full of extraordinary companies that at some point saw competition eat away at market share, reduce margins, and force them to scale back their ambitions. Selling in time doesn’t mean no longer believing in their merits, but recognizing that even leaders have to contend with the competitive cycle.

Cosa e quando vendere: ciclici vs crescita

Nel caso delle aziende cicliche il discorso è ancora più affascinante. Qui non conta tanto quanto guadagnano oggi, ma dove siamo nel ciclo. L’acciaio, l’energia, i semiconduttori: settori notoriamente soggetti a oscillazioni legate all’economia globale. Lynch suggerisce di osservare segnali che spesso arrivano prima dei bilanci: l’inflazione che accelera, i prezzi delle materie prime che cambiano direzione, le aziende che iniziano una guerra di prezzi per difendere le quote di mercato. Sono tutti sintomi che l’apice del ciclo potrebbe essere vicino. Chi investe in società cicliche deve saper accettare una verità scomoda: non si può possederle per sempre, bisogna avere il coraggio di vendere quando il mercato è euforico e comprare quando è depresso. È il contrario di ciò che l’emotività ci suggerisce, ma è così che si ottengono i migliori risultati.

Ancora più insidiosa è la tentazione di tenere all’infinito le cosiddette growth stocks, le società in forte crescita. Sono quelle di cui tutti parlano, i titoli che finiscono sulle copertine dei giornali finanziari e che generano vere e proprie fasi di culto. Anche qui, Lynch è chiaro: non bisogna innamorarsi di un titolo. Se il prezzo riflette già scenari di crescita irrealistici, se tutti gli analisti sono unanimi nel raccomandarlo e se i margini iniziano a comprimersi, allora forse il grosso del potenziale è già stato catturato. La storia è piena di aziende straordinarie che a un certo punto hanno visto la concorrenza rosicchiare quote di mercato, ridurre i margini e costringere a ridimensionare le ambizioni. Vendere in tempo non significa non credere più nella loro bontà, ma riconoscere che anche i leader devono fare i conti con il ciclo competitivo.

Companies undergoing restructuring and slow-growth stocks

Another crucial category is turnaround companies. Here, the psychological element is even stronger, because those who buy these stocks often do so at a time when pessimism reigns. By the time, turnaround story becomes clear to everyone, the price has already incorporated most of the expectations. Lynch advises paying attention to signals that can be gleaned from the numbers: inventories growing too fast relative to sales, debt rising again, the idea of a turnaround becoming mainstream. These are signs that market is about to turn the page, and those who believed in the recovery must have the clarity to cash in and move elsewhere.

The case of asset play companies is still different and particularly interesting for sophisticated investors. Here, the value is often hidden: undervalued land, a license, an energy reserve. When these assets are finally recognized and priced by the market, or when significant tax advantages disappear, time to exit may be near. A very concrete signal that Lynch highlights is the increase in institutional ownership above certain thresholds: when large investors have discovered the value, there is unlikely to be any further information advantage for small investors.

Finally, slow-growing companies, which many buy for the dividend, should not be underestimated. Here, the risk is falling asleep: collecting regular coupons can give a sense of security that is actually illusory. If company no longer innovates, loses ground, reduces spending on research and development, or pays unsustainable dividends, the threat is just around the corner. Financial history is full of stocks considered «widows and orphans» that dramatically disappointed those who held them out of inertia.

Aziende in ristrutturazione e titoli a crescita lenta

Un’altra categoria cruciale sono le turnaround companies, ovvero le società in ristrutturazione. Qui l’elemento psicologico è ancora più forte, perché spesso chi compra questi titoli lo fa in una fase in cui regna il pessimismo. Quando la storia del rilancio diventa evidente a tutti, il prezzo ha già incorporato gran parte delle aspettative. Lynch consiglia di prestare attenzione a segnali che si colgono nei numeri: scorte che crescono troppo velocemente rispetto alle vendite, debito che torna a salire, l’idea di turnaround che ormai è mainstream. Sono indizi che il mercato sta per voltare pagina, e chi ha creduto nel recupero deve avere la lucidità di incassare e spostarsi altrove.

Il caso delle asset play companies è ancora diverso e particolarmente interessante per gli investitori sofisticati. Qui il valore spesso è nascosto: un terreno sottovalutato, una licenza, una riserva energetica. Quando questi asset vengono finalmente riconosciuti e prezzati dal mercato, o quando vantaggi fiscali importanti vengono meno, il momento per uscire potrebbe essere vicino. Un segnale molto concreto che Lynch evidenzia è l’aumento della proprietà istituzionale oltre certe soglie: quando i grandi investitori hanno scoperto il valore, difficilmente ci sarà ancora un vantaggio informativo per il piccolo investitore.

Infine, non bisogna sottovalutare le aziende a crescita lenta, che molti acquistano per il dividendo. Qui il rischio è addormentarsi: incassare cedole regolari può dare un senso di sicurezza che in realtà è illusorio. Se l’azienda non innova più, perde terreno, riduce la spesa in ricerca e sviluppo o paga dividendi insostenibili, la minaccia è dietro l’angolo. La storia finanziaria è piena di titoli considerati «vedove e orfani» che poi hanno deluso drammaticamente chi li teneva solo per inerzia.

Selling is a strategic choice, not tactical

What unites all these scenarios is the underlying concept: selling is a strategic choice, not a tactical one. It is not about guessing top or bottom, nor is it about chasing the perfect stroke of luck. Rather, it is about recognizing the signs, interpreting the changing story and acting before the market, with its brutality, decides for us. This awareness requires discipline, clarity, and above all, the ability to put your life path at the center of the investment process.

During your financial life, there will inevitably come a time when you will have to liquidate some of your assets. Not only for market reasons or to take profits, but because life evolves and with it your needs change: retirement approaching, a family project to finance, desire to reduce risk after years of market exposure, or simply to enjoy what you have built. Thinking that a well-structured portfolio lives on accumulation alone is a dangerous illusion: the art of dismantling, when necessary, is as important as that of building.

The real skill lies not in buying the stock of the century, but in knowing how to sell it at the right time for you. It is a process requires courage because it involves going against the dominant emotions, both the fear of selling too soon and fear of exiting too late. Yet, as Lynch points out, market doesn’t know your life, your needs, or your dreams. It is your decisions must know it deeply, not the other way around. In this sense, selling is never an isolated act but part of a broader wealth management strategy. It is the culmination of a process takes into account the fundamentals of the stocks, phase of economic cycle and, above all, your personal history. Money only makes sense if it serves your goals and market becomes an extraordinary tool when you use it to live better, not when you become its prisoner.

Recognizing when to divest is an act of freedom: the freedom to choose according to your own rules and not those dictated by daily price movements. It means turning numbers into opportunities, profits on paper into real resources for your life. This is where the experience of investors like Lynch becomes invaluable: not to provide you with foolproof formulas, but to remind you that behind every chart there is always a person, with their own needs and timing. So the question «Where to Sell» is not just a technical question, but a broader reflection: where and when to sell depends as much on the market as on the meaning you attribute to your capital. Those who manage to integrate these two dimensions, the financial and existential, not only achieve better results, but also build a healthy relationship with money. Because, after all, the goal is not to be right about the market, but to be right in your own life.

Vendere è una scelta strategica, non tattica

Ciò che unisce tutti questi scenari è il concetto di fondo: vendere è una scelta strategica, non tattica. Non si tratta di giocare a indovinare il massimo o il minimo, né di inseguire il colpo di fortuna perfetto. Si tratta piuttosto di riconoscere i segnali, di interpretare la storia che sta cambiando e di agire prima che sia il mercato, con la sua brutalità, a decidere al posto nostro. Questa consapevolezza richiede disciplina, lucidità e soprattutto la capacità di mettere il proprio percorso di vita al centro del processo di investimento.

Nel corso della tua vita finanziaria, arriverà inevitabilmente il momento in cui dovrai liquidare parte dei tuoi asset. Non soltanto per ragioni di mercato o per prese di profitto, ma perché la vita evolve e con essa cambiano i tuoi bisogni: la pensione che si avvicina, un progetto familiare da finanziare, il desiderio di ridurre il rischio dopo anni di esposizione al mercato, oppure semplicemente la volontà di godere di ciò che hai costruito. Pensare che un portafoglio ben strutturato viva di sola accumulazione è un’illusione pericolosa: l’arte di smontare, quando serve, è tanto importante quanto quella di costruire.

La vera bravura non sta nel comprare il titolo del secolo, ma nel saperlo vendere al momento giusto per te. È un processo che richiede coraggio perché implica andare contro le emozioni dominanti, sia la paura di vendere troppo presto sia quella di uscire troppo tardi. Eppure, come ricorda Lynch, il mercato non conosce la tua vita, le tue necessità, i tuoi sogni. Sono le tue decisioni a doverlo conoscere profondamente e non il contrario. In questo senso, vendere non è mai un atto isolato ma fa parte di una strategia più ampia di gestione della ricchezza. È il punto di arrivo di un ragionamento che tiene conto dei fondamentali dei titoli, della fase del ciclo economico e, soprattutto, della tua storia personale. Il denaro ha senso solo se è al servizio dei tuoi obiettivi, e il mercato diventa uno strumento straordinario quando lo usi per vivere meglio, non quando diventi suo prigioniero.

Riconoscere il momento di disinvestire è un gesto di libertà: la libertà di scegliere in base alle tue regole e non a quelle dettate dall’andamento giornaliero delle quotazioni. Significa trasformare i numeri in opportunità, i profitti sulla carta in risorse reali per la tua vita. È qui che l’esperienza degli investitori come Lynch diventa preziosa: non per fornirti formule infallibili, ma per ricordarti che dietro ogni grafico c’è sempre una persona, con i suoi bisogni e i suoi tempi. E allora la domanda «Where to Sell» non è solo un interrogativo tecnico, ma una riflessione più ampia: dove e quando vendere dipendono tanto dal mercato quanto dal significato che attribuisci al tuo capitale. Chi riesce a integrare queste due dimensioni, quella finanziaria e quella esistenziale, non solo ottiene risultati migliori, ma costruisce un rapporto sano con il denaro. Perché, in fondo, l’obiettivo non è avere ragione sul mercato, ma avere ragione nella propria vita.