Going Back Through the Years

From Wall Street crash of 1929 to the pandemic of 2019. A brief history of 90 years of markets: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes

Financial markets have always absorbed changes in the mood of participants. We often forget that downturns are part of market trends, they are not an anomaly or defect, they simply happen. Similarly, the causes that trigger financial crises have been the same for hundreds of years. Just remember in 1929: thinking back to those days on Wall Street gives one full awareness of what risks are if one is not sufficiently equipped. Reviewing history is the first step toward awareness in the investment world. Let's dig in.

I mercati finanziari da sempre assorbono i cambiamenti d’umore dei partecipanti. Spesso dimentichiamo che i ribassi fanno parte dell’andamento del mercato, non sono un’anomalia o un difetto, semplicemente accadono. Allo stesso modo, le cause che scatenano le crisi finanziarie sono le stesse da centinaia di anni. Basti ricordarsi quella del 1929: ripensare a quelle giornate a Wall Street dà piena coscienza di quali sono i rischi che si corrono se non si è sufficientemente attrezzati. Ripercorrere la storia è il primo passo verso la consapevolezza nel mondo degli investimenti. Approfondiamo.

From Black Tuesday (1929) to the pandemic of 2019

On October 29, 1929, «Black Tuesday» hit Wall Street and investors traded about 16 million stocks in a single day and billions of dollars were lost. As a result of this day, United States and the rest of industrialized world plunged into the Great Depression (1929-39), the deepest and longest-lasting economic recession in recorded Western world history. Analyzing the causes behind the events and looking at their effects, why did the stock market crash in 1929?

During 1920s, the U.S. stock market underwent a rapid expansion, peaking in August 1929 after a period of wild speculation. By that time, production had already declined causing unemployment to rise and letting stock prices far exceed their real value. Other causes of the 1929 stock market crash included low wages, proliferation of debt, a struggling agricultural sector, and an excess of large bank loans that could not be liquidated. Stock prices began to fall in September, and on October 18 the real crash began. As the panic spread, on October 24 known as "Black Thursday," a record nearly 13 million shares were traded. Investment firms and major bankers attempted to stabilize the market by buying large blocks of shares, producing a moderate rally on Friday. On the following Monday, however, the storm raged again causing disastrous collapse of the New York Stock Exchange: on Black Tuesday (Oct. 29, 1929) stock prices collapsed completely and in a single day over 16 million shares were traded. Billions of dollars were lost, wiping out thousands of investors. Stock tickers fell hours behind because the machinery could not handle the tremendous volume of trading.

The effects of 1929 stock market crash resulted in a Great Depression. Following October 29, stock prices could only rise, allowing for a remarkable recovery during the following weeks. Prices continued to fall, leading United States into the Great Depression. By 1932, stocks came to be worth about 20% of their value recorded in the summer of 1929. The stock market crash was not the only cause of the Great Depression, but it sharply accelerated the global economic collapse. By 1933, nearly half of America's banks had failed and unemployment affected 15 million people equivalent to 30% of the labor force at time.

Dal Martedì nero (1929) alla pandemia del 2019

Il 29 Ottobre 1929, il «Martedì nero» si abbatté su Wall Street e gli investitori scambiarono circa 16 milioni di azioni in un solo giorno e miliardi di dollari furono persi. In seguito a questa giornata, gli Stati Uniti e il resto del mondo industrializzato precipitarono nella Grande Depressione (1929-39), la più profonda e duratura recessione economica che la storia del mondo occidentale ricordi. Analizzando le cause dietro agli avvenimenti e osservandone gli effetti, perchè il mercato azionario è crollato nel 1929?

Durante gli anni '20, il mercato azionario statunitense subì una rapida espansione, raggiungendo il suo picco nell'Agosto del 1929 dopo un periodo di speculazione selvaggia. A quel punto la produzione era già diminuita facendo aumentare la disoccupazione e lasciando che il prezzo delle azioni superasse di gran lunga il loro valore reale. Tra le altre cause del crollo del mercato azionario del 1929 ricordiamo i bassi salari, la proliferazione del debito, un settore agricolo in difficoltà e un eccesso di ingenti prestiti bancari che non potevano essere liquidati. I prezzi delle azioni cominciarono a scendere a Settembre e il 18 Ottobre iniziò il vero e proprio crollo. Quando il panico si diffuse, il 24 Ottobre noto come «Giovedì nero», fu scambiato un record di quasi 13 milioni di azioni. Le società d'investimento e i principali banchieri tentarono di stabilizzare il mercato comprando grandi blocchi di azioni, producendo un moderato rally il Venerdì. Il Lunedì successivo, tuttavia, la tempesta si scatenò di nuovo causando il disastroso crollo della Borsa di New York: il Martedì nero (29 Ottobre 1929) i prezzi delle azioni crollarono completamente e in un solo giorno oltre 16 milioni di azioni vennero scambiate. Miliardi di dollari andarono persi, spazzando via migliaia di investitori. I ticker azionari rimasero ore indietro perché i macchinari non riuscivano a gestire il tremendo volume di scambi.

Gli effetti del crollo del mercato azionario del 1929 sfociarono in una Grande Depressione. A seguito del 29 Ottobre, i prezzi delle azioni non poterono che salire, permettendo un notevole recupero durante le settimane successive. I prezzi continuarono a scendere, portando gli Stati Uniti nella Grande Depressione. Nel 1932 le azioni arrivano a valere circa il 20% del loro valore registrato nell'estate del 1929. Il crollo del mercato azionario non fu l'unica causa della Grande Depressione, ma accelerò in modo netto il crollo economico globale. Nel 1933, quasi la metà delle banche americane era fallita e la disoccupazione interessava 15 milioni di persone equivalenti il 30% della forza lavoro del tempo.

Effects of pandemic in the financial system

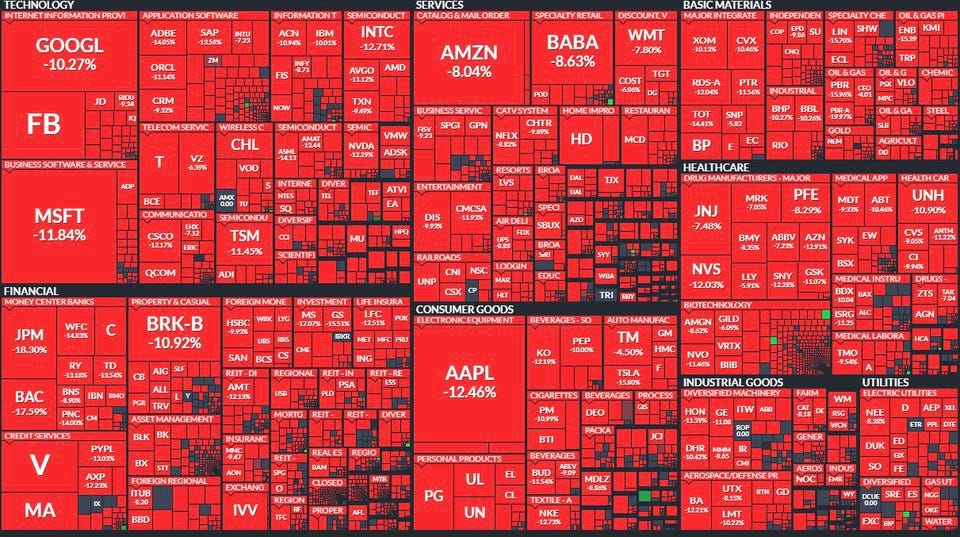

After 1929, the bear market developed between 1937 and 1950, 1966 and 1980, 2000 and 2008, arriving in 2019 with the onset of the pandemic in China, and everything changes, once again. Downturns are emotional is a well-known fact. Investors tend to throw away stocks the moment everything collapses, driven by fear. Conversely, during the phases of a wild bull market, greed pervades investors making them forget that best deal is at the best price, not at any price. In the months leading up to the pandemic, recurring attitude in the markets was more or less the usual one that financial analysts adopt during bullish phases: overconfidence. In the view of most, there was no cause for concern that stocks would collapse, and buying on absolute highs continued. Trading volumes of the major U.S. indices were good, making daily changes of +0.30%. Slow and relentless climb was the best way to entice new investors to enter the market thinking the game was simple.

A different scenario was emerging from China. New lockdown procedures affected entire housing areas, tens of millions of inhabitants, anticipating what Europe and then the World would soon experience as well. Fewer people in circulation meant less consumption; less consumption meant economic contraction. And here was the beginning of disaster that remains etched in our minds and carved into our lives. 2020 was the year that scarred so many traders and investors around the World. Working from home and a series of upheavals turned our lives upside down. Financial markets in a matter of months went from extreme crashes to doubling in value (from marked lows), fueled by the expansive stance of central banks.

Today we face a really difficult situation: huge amounts of debt that someone will have to repay, prices of goods and services doubled due to galloping inflation that has particularly affected food and energy. After every big slump we always start again as if nothing had happened because of human nature never changes. Since we have not adopted futuristic and self-sustaining policies but simply thrown the dust under the carpet (with Quantitative Easing), we can expect with mathematical certainty a new crisis. This is not a prophecy but simply calculation of probability applied to the series of events.

Gli effetti della pandemia nel sistema finanziario

Dopo il 1929 il mercato orso (ribassista) si sviluppò tra il 1937 e 1950, tra il 1966 e il 1980, ancora tra il 2000 e il 2008, arrivando al 2019 con l’inizio della pandemia in Cina, e tutto cambia, ancora una volta. Che i ribassi siano emotivi, è cosa nota. Gli investitori tendono a buttare via le azioni nel momento in cui tutto crolla, spinti dalla paura. Al contrario, durante le fasi di un mercato toro scatenato, l’avidità pervade gli investitori facendo loro dimenticare che il miglior affare si fa al miglior prezzo, non a qualunque prezzo. Nei mesi precedenti la pandemia, l’atteggiamento ricorrente sui mercati era più o meno il solito che gli analisti finanziari adottano durante le fasi di rialzo: l’eccessiva confidenza. A parere della maggior parte di questi, non c’erano motivi di preoccupazione che facessero pensare a un crollo delle azioni e gli acquisti sui massimi assoluti continuavano. I volumi di scambio dei principali indici americani erano buoni, facendo registrare ogni giorno variazioni dello +0,30%. La salita lenta e inesorabile era il miglior modo per invogliare nuovi investitori a entrare sul mercato pensando che il gioco fosse semplice.

Dai dati provenienti dalla Cina emergeva tutt’altro scenario. Le nuove procedure di lockdown interessavano intere aree abitative, decine di milioni di abitanti, anticipando quello che di lì a poco avrebbe vissuto anche l’Europa e poi il Mondo intero. Meno persone in circolazione significava meno consumi; meno consumi significava contrazione economica. Ed ecco l’inizio del disastro che rimane impresso nelle nostre menti e scolpito nelle nostre vite. Il 2020 è stato l’anno che ha segnato tantissimi trader e investitori di tutto il Mondo. Il lavoro da casa e una serie di sconvolgimenti hanno rivoltato le nostre vite. I mercati finanziari nel giro di pochi mesi sono passati da crolli estremi a raddoppiare di valore (dai minimi segnati), foraggiato dall’atteggiamento espansivo delle banche centrali.

Oggi ci troviamo ad affrontare una situazione davvero difficile: enormi quantità di debito che qualcuno dovrà ripagare, prezzi di beni e servizi raddoppiati a causa di un inflazione galoppante che ha colpito particolarmente cibo ed energia. Dopo ogni grande crollo si riparte sempre come se nulla fosse accaduto a causa della natura umana che non cambia mai. Non avendo adottato politiche futuristiche e auto-sostenibili ma semplicemente buttato la polvere sotto il tappeto (con il Quantitative Easing), possiamo aspettarci con matematica certezza una nuova crisi. Non è una profezia ma semplicemente il calcolo delle probabilità applicato alla serie degli eventi.

Lesson to be learned for the future

Entire economic sectors were wiped out, and reaction of the financial markets was devastating. Indeed, they have the ability to absorb reactions of traders in a very short time: with a single click it is possible to demonstrate feelings such as anguish and fear about what was happening. Some of the largest hedge funds declared bankruptcy, ETFs failed as a result of the dastardly, accommodative choices of central banks had accustomed the market to a state of liquidity addiction. Value segment in the United States was sold off as never before in history, and weeks that followed were subject to continuous oversold breaks. The misguided monetary policies had led us there served as fuel, fueling panic among traders. Leveraged exposure on the margin (with no real hedge countervalue) forced major market participants to succumb without having material time to absorb the outflow.

In those moments of absolute despondency the smart money, i.e., liquidity of knowledgeable investors, intervened: one must accept market declines, not become immune to them but view them as real opportunities to revalue one's capital. On average once a year there is a 10% drop in a few days or weeks and a 20% drop every 5-6 years. Accepting declines means paving the way to true returns. After every storm the sun returns, even in financial markets. Economic cycles follow wave patterns that recur again and again: alternating market corrections can foster impressive rises that last on average 5 times longer and yield returns 8 times higher.

The S&P500 index, global benchmark and reference for equity markets, has provided average returns in the past two decades that are higher than inflation, bonds, and any other asset. We go from lush moments to others with crises, depressions and more modest returns. But the long run doesn’t lie and result is a straight line. In these convulsive moments, the neophyte investor can end up sucked inside a spiral of uncontrollable events. Investor's focus should be to preserve capital and increase its value, certainly not to sell when the market goes down. The future is a question mark as one doesn’t know market dynamics, doesn’t have a clear investment plan, and tends to look for shortcuts with which to quickly achieve goals. Financial markets, on the other hand, require a lot of knowledge, and above all, patience. See you next episode!

La lezione da imparare per il futuro

Interi settori economici vennero spazzati via e la reazione dei mercati finanziari fu devastante. Essi hanno infatti la capacità di assorbire in pochissimo tempo le reazioni degli operatori: con un solo click è possibile dimostrare sentimenti come l’angoscia e la paura per quello che stava accadendo. Alcuni dei più grandi Hedge Funds dichiararono bancarotta, gli ETF fallirono come conseguenza delle scelte scellerate e accomodanti delle banche centrali che avevano abituato il mercato a uno stato di assuefazione da liquidità. Il comparto Value negli Stati Uniti venne venduto come mai nella storia e le settimane che seguirono furono soggette a continue interruzioni per eccesso di ribasso. Le maldestre politiche monetarie che ci avevano condotto fino a lì funsero da carburante, alimentando il panico tra gli operatori. L’esposizione con leva a margine (senza reale controvalore di copertura) costrinse i principali partecipanti al mercato a soccombere senza avere il tempo materiale di assorbire il flusso in uscita.

In quei momenti di assoluto sconforto intervennero gli smart money, vale a dire la liquidità degli investitori consapevoli: bisogna accettare i ribassi del mercato, non diventarne immune ma considerarli come vere occasioni per rivalutare il proprio capitale. Mediamente una volta l’anno c’è un ribasso del 10% in pochi giorni o settimane e uno del 20% ogni 5-6 anni. Accettare i ribassi significa aprire la strada verso il vero rendimento. Dopo ogni tempesta torna il sole, anche sui mercati finanziari. I cicli economici seguono dei modelli a onde che si ripresentano continuamente: l’alternanza delle correzioni di mercato può favorire rialzi imponenti che durano in media 5 volte più a lungo e rende i rendimenti 8 volte più alti.

L’indice S&P500, benchmark e riferimento mondiale dei mercati azionari, negli ultimi vent’anni ha garantito rendimenti medi superiori all’inflazione, all’obbligazionario e a qualsiasi altro asset. Si passa da momenti rigogliosi ad altri con crisi, depressioni e rendimenti più modesti. Ma il lungo periodo non mente e il risultato è una linea retta. In questi momenti convulsi, l’investitore neofita può finire risucchiato all’interno di una spirale di eventi incontrollabili. Il focus dell’investitore dovrebbe essere quello di preservare il capitale e aumentarne il valore, non certo vendere quando il mercato scende. Il futuro è un punto interrogativo in quanto non si conoscono le dinamiche di mercato, non si ha un piano d’investimento chiaro e si tende a cercare scorciatoie con cui raggiungere velocemente degli obiettivi. I mercati finanziari, invece, richiedono tanta conoscenza, e soprattutto pazienza. Al prossimo episodio!