Does Investing in Bonds Pay Off?

A brief guide to risks, returns and prospects

In finance, a bond is a debt security, issued by corporations or public entities, that at a fixed maturity gives its holder the right to repayment of the principal amount lent to the issuer plus interest on this principal amount. For the holder, bond is a form of investment represented by a financial instrument; for the issuer, on the other hand, purpose of the bond is to raise liquidity.

Until 2020 with interest rates near zero, bonds were not fashionable. After the ECB in Europe and Federal Reserve in the United States began the gradual process of raising interest rates, this financial instrument literally came back to life, and, at least until last year, investment in government and corporate bonds was powerfully back on the crest of the wave.

In finanza un'obbligazione è un titolo di credito, emesso da società o enti pubblici, che alla scadenza prefissata attribuisce al suo possessore il diritto al rimborso del capitale prestato all'emittente più un interesse su questo capitale. Per il possessore l'obbligazione è una forma di investimento rappresentata da uno strumento finanziario, per l'emittente invece il prestito obbligazionario ha il fine del reperimento di liquidità.

Fino al 2020 con i tassi d’interesse vicino allo zero, le obbligazioni non erano di moda. Dopo che la BCE in Europa e la Federal Reserve negli Stati Uniti hanno iniziato il processo graduale di rialzo dei tassi d’interesse, questo strumento finanziario ha ripreso letteralmente vita e, almeno fino all’anno scorso, l’investimento in titoli di stato e obbligazioni societarie è tornato prepotentemente sulla cresta dell’onda.

Benefits and risks of investing in bonds

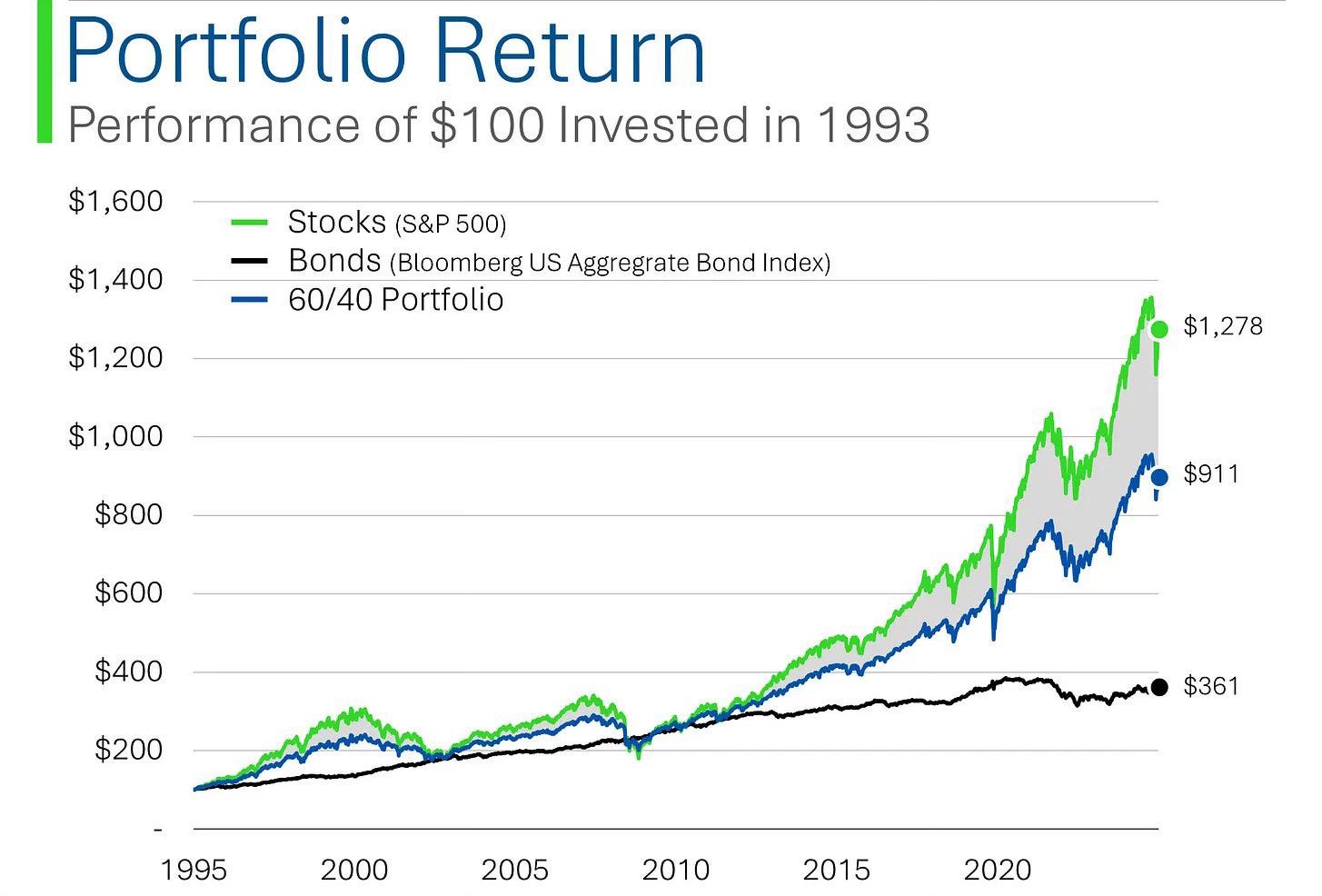

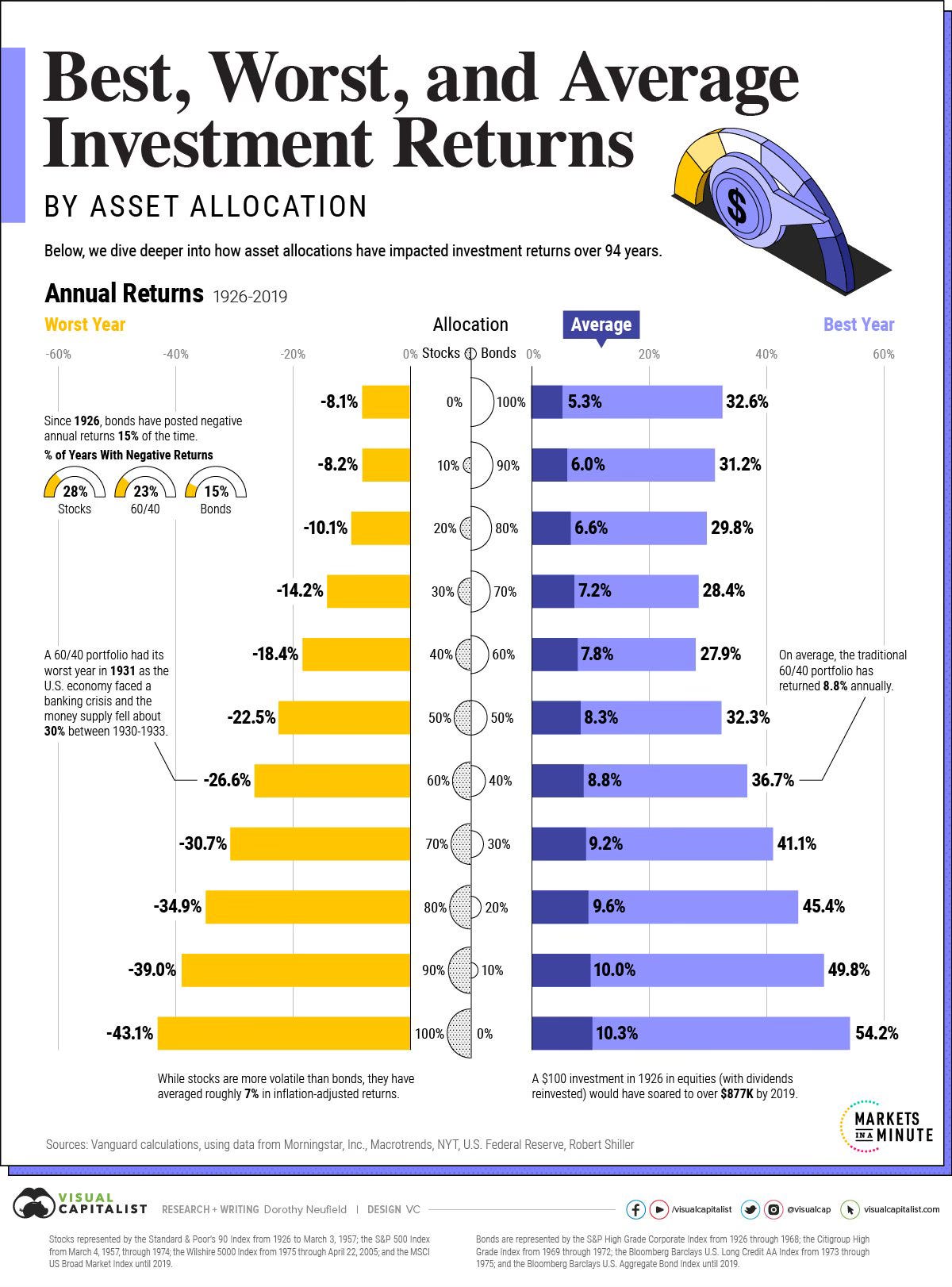

Without going too far into notions, the advantages of investing in bonds are many. They can provide a fixed income with periodic returns, have a high degree of solvency, and, with a stable rate curve, should experience less fluctuation (in price and yield, ed.) and therefore less volatility. They also make it possible to diversify a portion of the portfolio by making it more defensive, are less susceptible to exogenous factors, and are more protective of savings during phases of economic uncertainty, such as during a recession. It would seem to have found the holy grail, but in fact all that glitters is not gold, and bonds also have risks to consider.

The change in the interest rate is crucial. When rates go up, bond prices go down, in a phenomenon that in financial mathematics is called the «inverse relationship between price and yield». Another reason is credit risk, or possibility of issuer default. This, although remote, must be considered when underwriting a government bond. In fact, sovereign insolvency, which is the condition in which a state comes into which is no longer able to fully repay its public debt to its creditors, is not a rare case in history. The cause of a failure of a sovereign state is always attributable to a public deficit, that is, a situation in which state financial revenues, typically in the form of taxation, are insufficient to cover public expenditures, as happened to postwar Germany in 1945 and famous Argentine bonds in 2014.

One of the institutional parameters for identifying the degree of issuer solvency is the rating by agencies, such as Moody's, Standard and Poor's and Fitch. In my opinion, however, one of the best indicators is trivially the yield: higher the yield, higher the solvency risk, or at any rate, further away the date when you will be repaid the initial principal. Therefore, you should know for your information there is a mathematical relationship between price and yield to maturity. Without going into technicalities, it is very difficult to unearth inefficiencies among government bond prices: for this and other technical reasons, «bonds traders» as opposed to stock traders, are considered smart money, because they quickly price the real value of an asset in relation to the underlying risk.

Another inherent risk associated with bonds is inflation risk, which can erode the real value of yield. Every country or geographic area in the world has its own inflation linked to the currency in circulation. Consequently, foreign exchange risk is also another element of instability, especially for those who invest in foreign bonds. Banks, brokers and institutional have partially solved this issue by creating synthetic instruments that negate the exchange rate risk (EUR or USD Hedged, ed.) but add another cost element to the product offered.

Vantaggi e rischi nell’investimento in obbligazioni

Senza scendere troppo nel nozionismo, i vantaggi di investire in obbligazioni sono molteplici. Possono garantire un reddito fisso con cedole periodiche, hanno un alto grado di solvibilità e, con una curva dei tassi stabili, dovrebbero subire minori oscillazioni (di prezzo e di rendimento, ndr) e quindi meno volatilità. Inoltre permettono di diversificare una parte del portafoglio rendendolo più difensivo, sono meno soggetti a fattori esogeni e proteggono maggiormente i risparmi nelle fasi di incertezza economica, come ad esempio durante una recessione. Sembrerebbe aver trovato il Sacro Graal, ma in realtà non è tutto oro quello che luccica e anche le obbligazioni hanno dei rischi da considerare.

La variazione del tasso d’interesse è determinante. Quando i tassi salgono i prezzi delle obbligazioni scendono, in un fenomeno che in matematica finanziaria è definito «relazione inversa tra prezzo e rendimento». Un altro motivo è il rischio di credito, ovvero le possibilità di default dell’emittente. Tale possibilità, sebbene remota, è da considerare quando si sottoscrive un titolo di stato. Infatti l’insolvenza sovrana, che è la condizione in cui viene a trovarsi uno Stato che non è più in grado di restituire completamente il suo debito pubblico ai creditori, non è un caso raro nella storia. La causa di un fallimento di uno Stato sovrano è sempre ascrivibile a una situazione di deficit pubblico, cioè una situazione in cui le entrate finanziarie statali, tipicamente sotto forma di tassazione, risultano insufficienti a coprire le uscite pubbliche, come successo alla Germania del dopo-guerra nel 1945 e ai famosi bonds Argentini nel 2014.

Uno dei parametri istituzionali per identificare il grado di solvibilità dell’emittente è la valutazione da parte delle agenzie di rating, come ad esempio Moody's, Standard and Poor's e Fitch. A mio parere però uno dei migliori indicatori è banalmente il rendimento: più alto è il rendimento più alto è il rischio di solvibilità o comunque, più è lontana la data in cui ti verrà rimborsato il capitale iniziale. Pertanto, bisogna sapere a titolo informativo che esiste una relazione matematica tra il prezzo e il rendimento a scadenza. Senza scendere in tecnicismi, è molto difficile scovare inefficienze tra i prezzi dei titoli di stato: per questo e altri motivazioni tecniche, i «bonds trader» al contrario di quelli azionari, sono considerati smart money (investitori intelligenti, ndr) perché prezzano velocemente il reale valore di un asset in relazione al rischio sottostante.

Un altro rischio intrinseco collegato alle obbligazioni è quello dell’inflazione che può erodere il valore reale del rendimento. Ogni paese o area geografica del mondo ha la sua inflazione collegata alla moneta circolante. Di conseguenza anche il rischio cambio è un altro elemento di instabilità, soprattutto per coloro che investono in obbligazioni estere. Gli intermediari e gli emittenti hanno risolto parzialmente questa problematica, creando degli strumenti sintetici che annullano il rischio cambio (EUR o USD Hedged, ndr) ma che aggiungono un altro elemento di costo al prodotto offerto.

The current historical context

Now we know in general terms what bonds are and how they work, it may be useful to put them in context in today's economic landscape. The various eras and economic cycles show that each period is very different from one another. Although some events keep repeating themselves (crises, wars, natural disasters, new scientific discoveries, technological development, etc etc) history is very mixed. For example, during the economic boom of the 1960s, bond yields in Italy were generally high, often between 10% and 15%. However, high inflation, in some periods even above 25%, tended to greatly reduce real investment returns. In recent years and for so long from Mario Draghi's «Whatever It Takes» of 2008 onward, Quantitative Easing and resulting zero rate has been the norm. So what is appropriate to do today?

Truth as is often the case there’s no general rule applies to every season of interest rate trends. Each period has a correlation, sometimes positive and sometimes negative, with respect to assets defined as riskier such as the stock market. If economists were always right, we would all be rich. Financial markets by their very nature are made to surprise, constantly incorporating new information, and like water that adapts to its container, markets continue to adapt, remaining in a chaotic balance between the pressures of buyers and sellers trading on the books each day.

As a general rule of thumb, and particularly after monetary tightening from 2022 to the present, it might be appropriate to veer toward short and mid-term bonds, not going beyond 5-10 years and leave the opportunity seekers with mature bonds (long and very long maturities, ed.). On the other hand, we live in such a changeable environment that it might be inconvenient to set a yield at 3%, when interest rates might experience a sudden surge and thus a decline in the price of underlying asset. The offerings of most banks tend to return all or part of the rate set by European Central Bank; it might therefore be a good solution in the short term to use a deposit account to capitalize on a minimum return and remain slightly positive above inflation. These solutions remain very entry level and useful for novice investors, who are often risk averse and very conservative. There are more complex plans and strategies that, if properly mixed, can provide the same degree of protection and return, but is not the focus of this article.

Il contesto storico attuale

Adesso che conosciamo in linea generale cosa sono e come funzionano le obbligazioni, può essere utile contestualizzarle nel panorama economico attuale. Le varie epoche e i cicli economici dimostrano che ogni periodo è molto diverso uno dall’altro. Sebbene alcuni eventi continuino a ripetersi (crisi, guerre, calamità naturali, nuove scoperte scientifiche, sviluppo tecnologico, ecc. ecc.) la storia è molto variegata. Ad esempio durante il boom economico degli anni '60, i rendimenti obbligazionari in Italia erano generalmente elevati, spesso tra il 10% e il 15%. Tuttavia, l'inflazione elevata, in alcuni periodi anche superiore al 25%, tendeva a ridurre notevolmente il rendimento reale degli investimenti. Negli anni recenti e per tanto tempo dal «Whatever It Takes» del 2008 di Mario Draghi in poi, il Quantitative Easing e il conseguente tasso zero è stato la normalità. Quindi cosa conviene fare oggi?

La verità come spesso accade è che non c’è una regola generale che vale per ogni stagione di andamento dei tassi d’interesse. Ogni periodo è caratterizzato da una correlazione, a volte positiva e a volte negativa, rispetto ad asset definiti più rischiosi come il mercato azionario. Se gli economisti avessero sempre ragione, saremo tutti ricchi. I mercati finanziari per loro natura sono fatti per sorprendere, inglobano continuamente nuove informazioni e, come l’acqua che si adatta al suo contenitore, anche i mercati continuano ad adattarsi, rimanendo in un caotico equilibrio tra le pressioni di compratori e venditori che ogni giorno scambiano sui book di negoziazione.

Come regola generale, e in particolare dopo la stretta monetaria dal 2022 ad oggi, potrebbe essere opportuno virare verso obbligazioni a breve e medio termine, non andando oltre i 5-10 anni e lasciare agli opportunity seeker i bond matusalemme (a lunga e lunghissima scadenza, ndr). Dall’altra parte, viviamo in un contesto così mutevole che potrebbe essere sconveniente fissare un rendimento al 3%, quando i tassi d’interesse potrebbero subire un improvvisa impennata e quindi una diminuzione di prezzo del sottostante. Le offerte della maggior parte degli intermediari tendono a restituire tutto o in parte del tasso stabilito dalla Banca Centrale Europea; potrebbe pertanto essere una buona soluzione nel breve periodo quella di utilizzare un conto deposito per capitalizzare un rendimento minimo e mantenersi leggermente positivi sopra l’inflazione. Queste soluzioni rimangono molto entry level e utili per investitori alle prime armi, spesso poco avversi al rischio e molto conservativi. Esistono piani e strategie più complesse che se opportunamente mixate, possono garantire lo stesso grado di protezione e rendimento, ma non è il focus di questo articolo.

Conclusions

The investor's profile remains the real key parameter to know in order to build a tailored suit. Risk tolerance and life goals are the pillars on which to build what I call a «generational portfolio». Periods of zero rates have discouraged investment in bonds while those with higher rates have attracted investors and speculators who, however, are also often ignorant of the risks involved. Buying blindly is always the worst thing to do: if an asset is cheap there must be a reason, right? There are many assessments to be made, and generally run counter to what could be done using common sense. Finance and capital markets in particular are counter-intuitive, and although they were created to finance companies, nations and forage for asset management industry, they have very complex logic that an ordinary investor cannot fully understand.

Navigating by sight during phases of uncertainty or, better yet, relying on an experienced advisor could be one of the solutions, but not the only one. Each of us has priorities and life and wealth goals, short or long term. Even there is a large part of the population that has no financial goals, partly because of a poor money culture and partly because they «couldn't care less». All fair and all in line with what one wants and can do with one's money. The key thing to know is that risk is the only propellant for performance: although this is a double-edged sword, it is the only way to create a fulfilling performance in the long run.

Conclusioni

Il profilo dell’investitore rimane il vero parametro fondamentale da conoscere per poter costruire un vestito su misura. La tolleranza al rischio e gli obiettivi di vita sono i pilastri su cui partire per la creazione di quello che io definisco «portafoglio generazionale». I periodi di tassi zero hanno scoraggiato l’investimento in obbligazioni mentre quelli con tassi più alti hanno attratto investitori e speculatori che spesso però ignorano anche i rischi connessi. Comprare alla cieca è sempre la cosa peggiore da fare: se un asset costa poco ci sarà un motivo, no? Le valutazioni da fare sono molteplici e in generale sono in controtendenza rispetto a quello che si potrebbe fare usando il buon senso. La finanza e i mercati di capitali in particolare sono contro-intuitivi e, nonostante siano stati creati per finanziare aziende, nazioni e foraggiare l’industria del risparmio gestito, hanno delle logiche molto complesse che un investitore comune non riesce a comprendere del tutto.

Navigare a vista durante le fasi di incertezza o meglio ancora, affidarsi ad un consulente esperto potrebbe essere una delle soluzioni, ma non l’unica. Ognuno di noi ha delle priorità e degli obiettivi di vita e patrimoniali, di breve o lungo termine. Addirittura c’è una gran parte della popolazione che non ha obiettivi finanziari, un pò per una scarsa cultura del denaro e un pò perchè «non gliene può fregar di meno». Tutto giusto e tutto in linea con quello che si vuole e si può fare col proprio denaro. La cosa fondamentale da sapere è che il rischio è l’unico propellente per il rendimento: sebbene questa sia un’arma a doppio taglio, è l’unica strada per creare una performance appagante nel lungo periodo.