Baumol's Cost Disease

The lesson is not limited to the present and offers us a model for guessing future directions of the economy

William Baumol, an economist who passed away in 2017 at the age of 95, is known for a famous theory called «Baumol's cost disease», which offers an interesting key to many dynamics of contemporary economics.

This theory elucidates, for example, why hairdressers earn higher wages in Milano than in Salerno, or why sectors such as health care and education turn out to be continually increasing in cost. It also provides a possible reason why affluent nations such as the United States employ an increasing share of its workforce in activities with low productive returns, thus holding back the overall pace of economic productivity growth. In the 1960s, while studying the arts sector, Baumol made an interesting observation: musicians were not becoming more productive, performing a string quartet piece required the same number of performers and same duration in 1965 as in 1865, but despite this, modern musicians' fees were significantly higher than in the past.

The logic behind this observation was quite intuitive. In other areas of the economy, such as industry, improvements in productivity were driving up wages. An arts organization had maintained musicians' wages in 1960 at the same levels as in 1860 would have found that musicians were leaving for better-paid occupations. As a result, arts organizations, at least those with sufficient resources, were forced to offer higher wages to retain top talent. This resulted in productivity gains in the industry indirectly driving up costs in labor-intensive services such as live concerts. Factories, with increased efficiency, can simultaneously raise wages and lower prices. But with wage growth, theaters and music venues have no choice but to raise ticket prices to bear the higher costs.

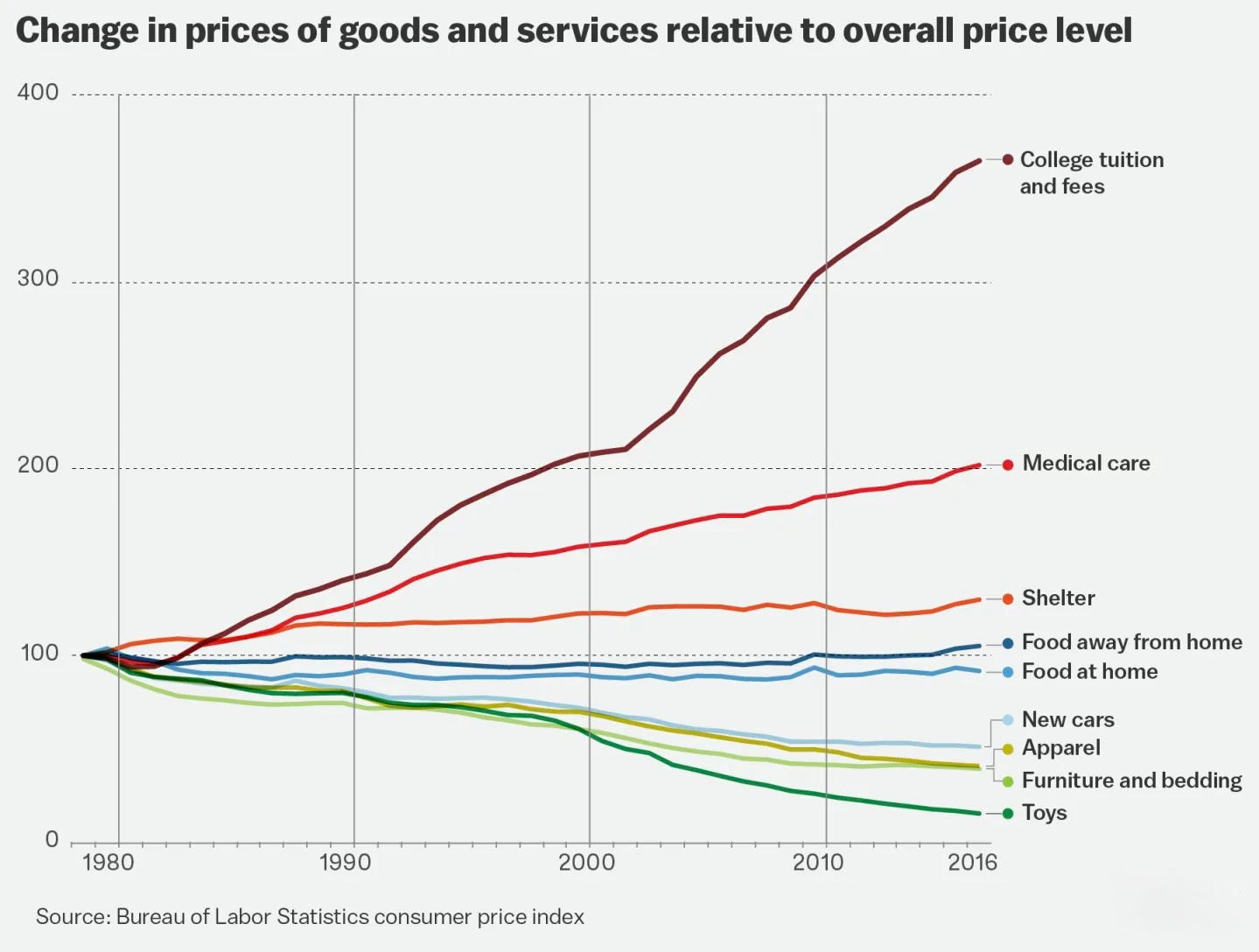

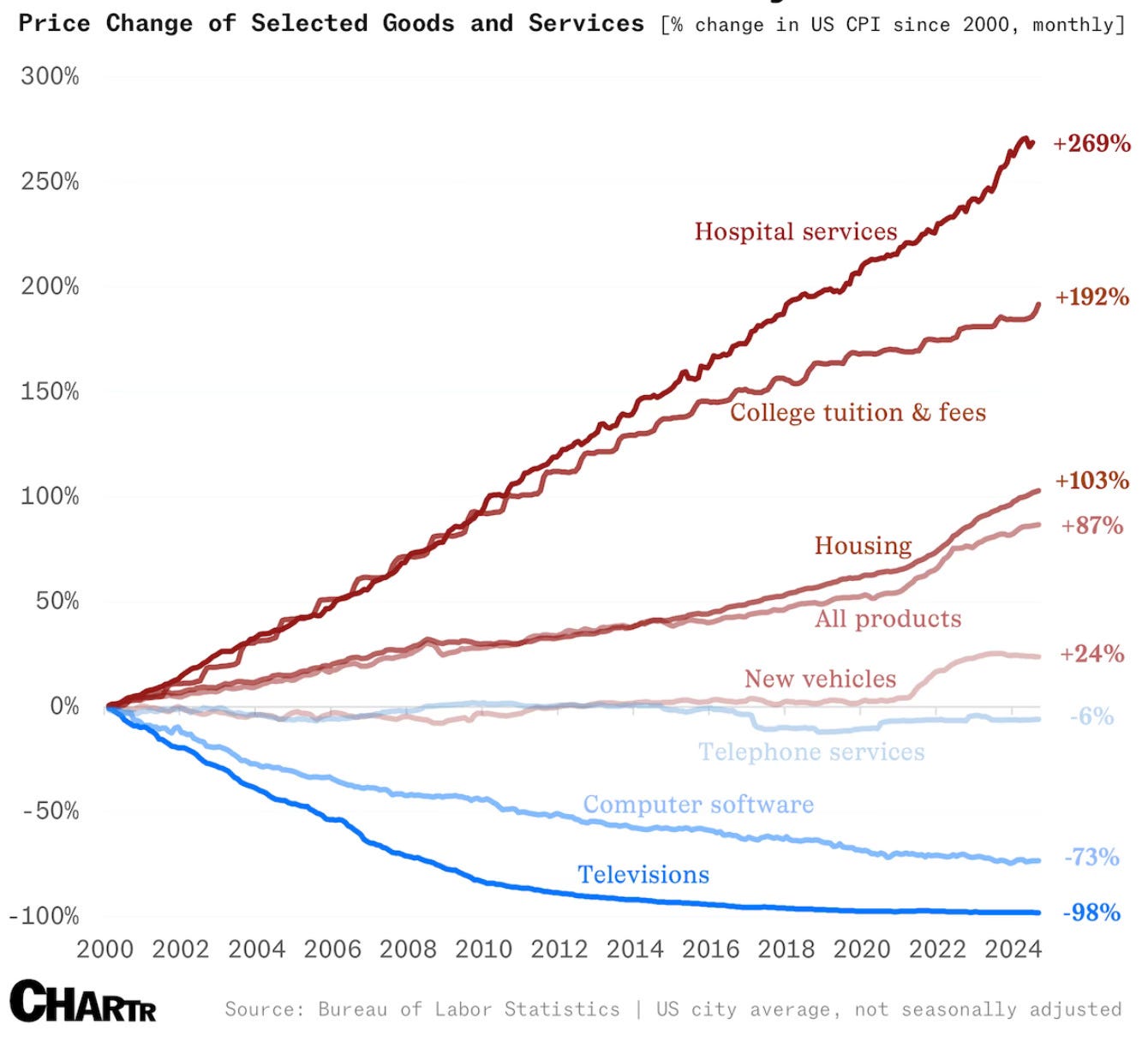

This mechanism has been called Baumol's cost disease, and he himself sensed its scope far beyond the arts sector. According to this theory, in a context of rapid technological development, we should expect a decline in prices for industrial goods, such as cars, telephones, clothing or fruit, and a concomitant rise in prices for services that require a lot of human labor, such as schooling, health care, child care, haircuts, personal training, legal assistance and so on. And this trend is exactly what economic statistics have confirmed. Over the decades, health care and education have soared in cost, while the price of cars, clothes, furniture, toys and other industrially produced goods has remained under control or even fallen relative to inflation: exactly as Baumol predicted half a century earlier.

His theory remains a useful tool for deciphering today's economic reality. He suggests to us, for example, the continued rise in costs in health care and education doesn’t necessarily indicate malfunctions in those sectors. Until we invent robotic doctors, teachers and nurses, it is likely these sectors will remain structurally expensive because of their low relative productivity. Although some believe that the price increases are caused by government aid, the same pattern is seen in private activities such as summer camps, veterinary services or theater performances, which operate outside government regulations or subsidies. Of course, as The Atlantic's Derek Thompson has pointed out, prices for many of these services are rising faster than wages, a sign that Baumol's theory doesn’t explain everything. Some universities, for example, have dramatically increased the number of managers and built lavish facilities to attract students. In addition, rising incomes among the wealthier segments of the population partly explain the growth in demand for exclusive amenities such as Broadway musicals, elite summer camps or access to prestigious universities.

But even assuming we can curb the soaring costs for these services, they are unlikely to become as cheap as T-shirts or televisions. Their labor-intensive nature necessarily makes them expensive, and those who work in these areas deserve a fair wage. As Steven Perlstein has argued, this dynamic has important policy consequences. Much of public budgets, both state and federal, are devoted to services, such as justice, schools, health care, law enforcement, which are subject to the cost disease. In recent decades, government spending on these items has grown steadily, and for many conservatives this is an indication of inefficiencies in the state system.

But according to Baumol's analysis, this is not a sign of dysfunction: it is simply an inevitable consequence, dictated by the very nature of these services, which over time tend to become more expensive in comparison to goods produced by private industry. In other words, rising costs in services is a physiological side effect of economic progress. It is unrealistic to think of maintaining the current standard of living by lowering spending in services to the levels of the 1950s.

William Baumol, economista scomparso nel 2017 all’età di 95 anni, è noto per una celebre teoria chiamata «malattia dei costi di Baumol», la quale offre una chiave di lettura interessante per molte dinamiche dell’economia contemporanea.

Questa teoria chiarisce, ad esempio, come mai i parrucchieri percepiscano salari più alti a Milano rispetto a Salerno, o per quale motivo settori come la sanità e l’educazione risultino in continuo aumento di costo. Fornisce anche un possibile motivo per cui nazioni benestanti come gli Stati Uniti impieghino una quota crescente della propria forza lavoro in attività con bassi rendimenti produttivi, frenando così il ritmo complessivo di crescita della produttività economica. Negli anni Sessanta, mentre studiava il settore delle arti, Baumol fece un’osservazione interessante: i musicisti non diventavano più produttivi, l’esecuzione di un brano per quartetto d’archi richiedeva lo stesso numero di esecutori e la stessa durata nel 1965 come nel 1865, ma nonostante ciò, i compensi dei musicisti moderni erano decisamente più elevati rispetto al passato.

La logica dietro questa osservazione era piuttosto intuitiva. In altri ambiti economici, come l’industria, i miglioramenti nella produttività stavano facendo aumentare i salari. Un ente culturale che nel 1960 avesse mantenuto i salari dei musicisti agli stessi livelli del 1860, avrebbe scoperto che questi ultimi lasciavano il posto per occupazioni meglio retribuite. Di conseguenza, le organizzazioni artistiche, almeno quelle con sufficienti risorse, sono state costrette a offrire salari più alti per trattenere i migliori talenti. Questo ha comportato che i guadagni di produttività nell’industria abbiano indirettamente determinato l’aumento dei costi in servizi intensivi in manodopera, come i concerti dal vivo. Le fabbriche, grazie alla maggiore efficienza, possono contemporaneamente aumentare gli stipendi e abbassare i prezzi. Ma con la crescita salariale, teatri e locali musicali non hanno altra scelta che aumentare i prezzi dei biglietti per sostenere i costi maggiori.

Questo meccanismo è stato definito malattia dei costi di Baumol, e lui stesso ne intuì la portata ben oltre il settore artistico. Secondo questa teoria, in un contesto di rapido sviluppo tecnologico, dovremmo aspettarci un calo dei prezzi per beni industriali, come automobili, telefoni, abbigliamento o frutta, e un contestuale rincaro dei servizi che richiedono molto lavoro umano, come la scuola, la sanità, la cura dell’infanzia, i tagli di capelli, l’allenamento personale, l’assistenza legale e così via. E questa tendenza è esattamente ciò che le statistiche economiche hanno confermato. Nel corso dei decenni, sanità ed educazione hanno subito un’impennata nei costi, mentre il prezzo di auto, vestiti, mobili, giocattoli e altri beni di produzione industriale si è mantenuto sotto controllo o è addirittura sceso rispetto all’inflazione: esattamente come Baumol aveva previsto mezzo secolo prima.

La sua teoria resta uno strumento utile per decifrare la realtà economica odierna. Ci suggerisce, per esempio, che l’aumento continuo dei costi in sanità e istruzione non indica necessariamente malfunzionamenti in quei settori. Finché non inventeremo dottori, docenti e infermieri robotici, è probabile che questi comparti restino strutturalmente costosi, a causa della loro bassa produttività relativa. Anche se alcuni ritengono che i rincari siano causati dagli aiuti pubblici, lo stesso schema si osserva in attività private come i campi estivi, i servizi veterinari o gli spettacoli teatrali, che operano al di fuori di regolamenti o sovvenzioni statali. Certo, come ha fatto notare Derek Thompson dell’Atlantic, i prezzi di molti di questi servizi stanno salendo più velocemente dei salari, segno che la teoria di Baumol non spiega tutto. Alcune università, ad esempio, hanno aumentato vertiginosamente il numero di dirigenti e costruito strutture lussuose per attrarre studenti. Inoltre, l’aumento del reddito tra le fasce più ricche della popolazione spiega in parte la crescita della domanda per servizi esclusivi come i musical di Broadway, i campi estivi d’élite o l’accesso alle università prestigiose.

Ma anche ipotizzando di riuscire a frenare l’impennata dei costi per questi servizi, è improbabile che diventino economici come le t-shirt o i televisori. La loro natura labor-intensive li rende necessariamente costosi, e chi lavora in questi ambiti merita una giusta retribuzione. Come ha sostenuto Steven Perlstein, questa dinamica ha importanti conseguenze politiche. Gran parte dei bilanci pubblici, sia statali che federali, è destinata a servizi, come giustizia, scuola, sanità, forze dell’ordine, soggetti alla malattia dei costi. Negli ultimi decenni, la spesa pubblica per queste voci è cresciuta costantemente, e per molti conservatori ciò è indice di inefficienze nel sistema statale.

Secondo l’analisi di Baumol ciò non è un segnale di disfunzione: è semplicemente una conseguenza inevitabile, dettata dalla natura stessa di questi servizi, che nel tempo tendono a diventare più costosi in confronto ai beni prodotti dall’industria privata. In altre parole, l’aumento dei costi nei servizi è un effetto collaterale fisiologico del progresso economico. È irrealistico pensare di mantenere l’attuale tenore di vita abbassando le spese nei servizi fino ai livelli degli anni Cinquanta.

Fast innovation, slow growth

Viewed from this perspective, an answer can be given to one of the most debated paradoxes of the U.S. economy: how it is possible for such fast innovation to coexist with relatively modest GDP growth. As industry has become more efficient, prices of many goods have fallen. But once we fill our closets and living rooms, spending on these goods falls, while their cost continues to fall.

And what do we do with the money saved? We allocate it to goods and services that are not following the same downward trajectory. People who live in metropolises like Milan or Rome probably spend a lot on rent. But for many people, a growing slice of income goes into services that require a lot of human labor: schooling, medical care, baby-sitting, restaurant meals and the like.

When productivity in a sector increases, wages in that sector naturally increase. This forces wages and prices of services don’t have higher productivity to rise in order to remain competitive. Thus, when a country becomes wealthier, goods become cheaper, but labor-intensive services, such as health care and college tuition, cost more.

The result is that a larger and larger share of economic activity is focused on these services, and an increasing number of workers are employed in them. The problem, however, is that if most of the workforce is employed in low-productivity sectors, such as nurses, babysitters or lawyers, even significant progress in the industry will not have a major effect on the overall rate of growth. On the contrary, innovation may accentuate this imbalance, driving consumers to direct more and more spending toward less productive services.

Of course, it could be argued that technological innovation will also be able to automate many jobs in the service sector, and this is already happening in part. Taxi drivers, for example, may be replaced in the next few years by autonomous vehicles. However, many professions in services are difficult to fully automate: few parents would willingly entrust their children to a nanny-robot, and no matter how sophisticated diagnostic software becomes, patients will still want doctors to explain and nurses to care for them.

Baumol's lesson, then, is not limited to the present: it also offers us a model for guessing future directions in the economy. He highlighted why services that require a lot of human staff tend to become more costly in a growing economy. And these services, in all likelihood, also represent the future of the world economy.

Innovazione veloce, crescita lenta

Visto da questa prospettiva, si può dare una risposta a uno dei paradossi più discussi dell’economia americana: come sia possibile che un’innovazione così veloce conviva con una crescita del PIL relativamente modesta. Con l’industria diventata più efficiente, i prezzi di molti beni sono scesi. Ma una volta riempiti i nostri armadi e salotti, la spesa per questi beni cala, mentre il loro costo continua a diminuire.

E cosa facciamo con i soldi risparmiati? Li destiniamo a beni e servizi che non stanno seguendo la stessa traiettoria discendente. Chi vive in metropoli come Milano o Roma probabilmente spende molto in affitto. Ma per molte persone, una fetta crescente del reddito va in servizi che richiedono molto lavoro umano: scuola, cure mediche, baby-sitting, pasti al ristorante e simili.

Quando la produttività di un settore aumenta, i salari di quel settore aumentano naturalmente. Questo costringe i salari e i prezzi dei servizi che non hanno una maggiore produttività ad aumentare per rimanere competitivi. Così, quando un Paese diventa più ricco, i beni diventano più economici, ma i servizi ad alta intensità di lavoro, come l'assistenza sanitaria e le rette universitarie, costano di più.

Il risultato è che una fetta sempre più ampia dell’attività economica si concentra su questi servizi, e un numero crescente di lavoratori vi trova impiego. Il problema, però, è che se la maggior parte della manodopera è occupata in settori a bassa produttività, come infermieri, babysitter o avvocati, anche un notevole progresso nell’industria non avrà effetti incisivi sul tasso generale di crescita. Anzi, l’innovazione potrebbe accentuare questo squilibrio, spingendo i consumatori a indirizzare sempre più spesa verso i servizi meno produttivi.

Certo, si potrebbe obiettare che l’innovazione tecnologica potrà automatizzare anche molti lavori nel terziario, e ciò in parte sta già accadendo. I tassisti, per esempio, potrebbero essere sostituiti nei prossimi anni da veicoli autonomi. Tuttavia, molte professioni nei servizi sono difficili da automatizzare completamente: pochi genitori affiderebbero volentieri i figli a una tata-robot, e per quanto sofisticati diventino i software diagnostici, i pazienti continueranno a volere medici che spieghino e infermieri che si prendano cura di loro.

La lezione di Baumol, dunque, non si limita al presente: ci offre anche un modello per intuire le direzioni future dell’economia. Ha messo in luce perché i servizi che richiedono molto personale umano tendano a diventare più onerosi in un’economia in crescita. E questi servizi, con ogni probabilità, rappresentano anche il futuro dell’economia mondiale.